I have done parts and episodes in my previous forays into the history of the silver screen, but I see the topic of Black American cinema as a study of two halves that make a superb whole. As the title might suggest, today we’re delving into the first half, namely the first fifty or so years of Black American filmmaking with an emphasis on the struggles of racial inequality and discrimination that have plagued the industry for so long. The issue has never really gone away, but at least it is less brutal than in the early 20th century. In other words, while the first half of Black American cinema is defined by pioneers and visionaries, it is also rife with racist tropes, constant difficulties with white financiers, as well as internal struggles regarding story and identity.

There was barely any room for Black Americans in the film business. If any of them wanted to make it to the big screen, they would have to become filmmakers themselves. Few were hired to play racially accurate roles, as most such positions were otherwise rare and usually went to white actors in blackface. And while the Lumiére brothers brought cinema to life with ‘Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat’ in 1896, it wasn’t until thirty years later that Stepin Fetchit became the first black person to receive a feature screen credit in a film. Sometime later, Hattie McDaniel was the first black person to win an Academy Award, though she wasn’t allowed to share a table at the Oscars with her fellow white co-stars. It was in 1964, barely, that Sidney Poitier made history as the first black man to take the same honour home.

STEPIN FETCHIT WITH WIFE DOROTHY STEVENSON (1929)

STEPIN FETCHIT WITH WIFE DOROTHY STEVENSON (1929)

Perhaps the best reference I might offer for early Black American film comes in the form of the ‘Pioneers of African American Cinema’ collection from the Criterion Channel, home to 34 films that were preserved and restored minutely for their historical value. Charles Musser and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart did a phenomenal job of curating this selection, which was released in 2016. It is a compelling example of the range of films produced mainly for segregated black audiences in the first half of the 20th century—better known as ‘race films’ that featured mainly all-black casts. Many were also made by Black American filmmakers. Ultimately, the true value of these productions was not to use their black subjects as props or objects of ridicule. Their premise brought their lives front and centre, giving voice to a community that had been kept out of the limelight for far too long, already.

Of Oscar Micheaux, True Pioneer

J. Ronald Green once wrote of the African American filmmaker that he hit a ‘straight lick with a crooked stick’, which accurately describes Oscar Micheaux’s cinematic ingenuity. He built his name on genres like the melodrama, the crime drama, and romance, producing 44 films to his name.

Among them, I’m compelled to bring up the embedded flashbacks from ‘Within Our Gates’ (1920), which offer complex and layered lives (and afterlives). Its crosscutting and temporal treatment speak against D.W. Griffith’s ‘The Birth of a Nation’ (1915). In a most brilliant move, Mr Micheaux uses Mr Griffith’s own language to disprove his racist claims by showing a reality that ‘The Birth of a Nation’ refused to address, despite its cinematic prowess. The Black American director depicts the white lynch mob as opposed to the romanticized gallant Klan, choosing to show a truth that black people knew, and white people refused to acknowledge.

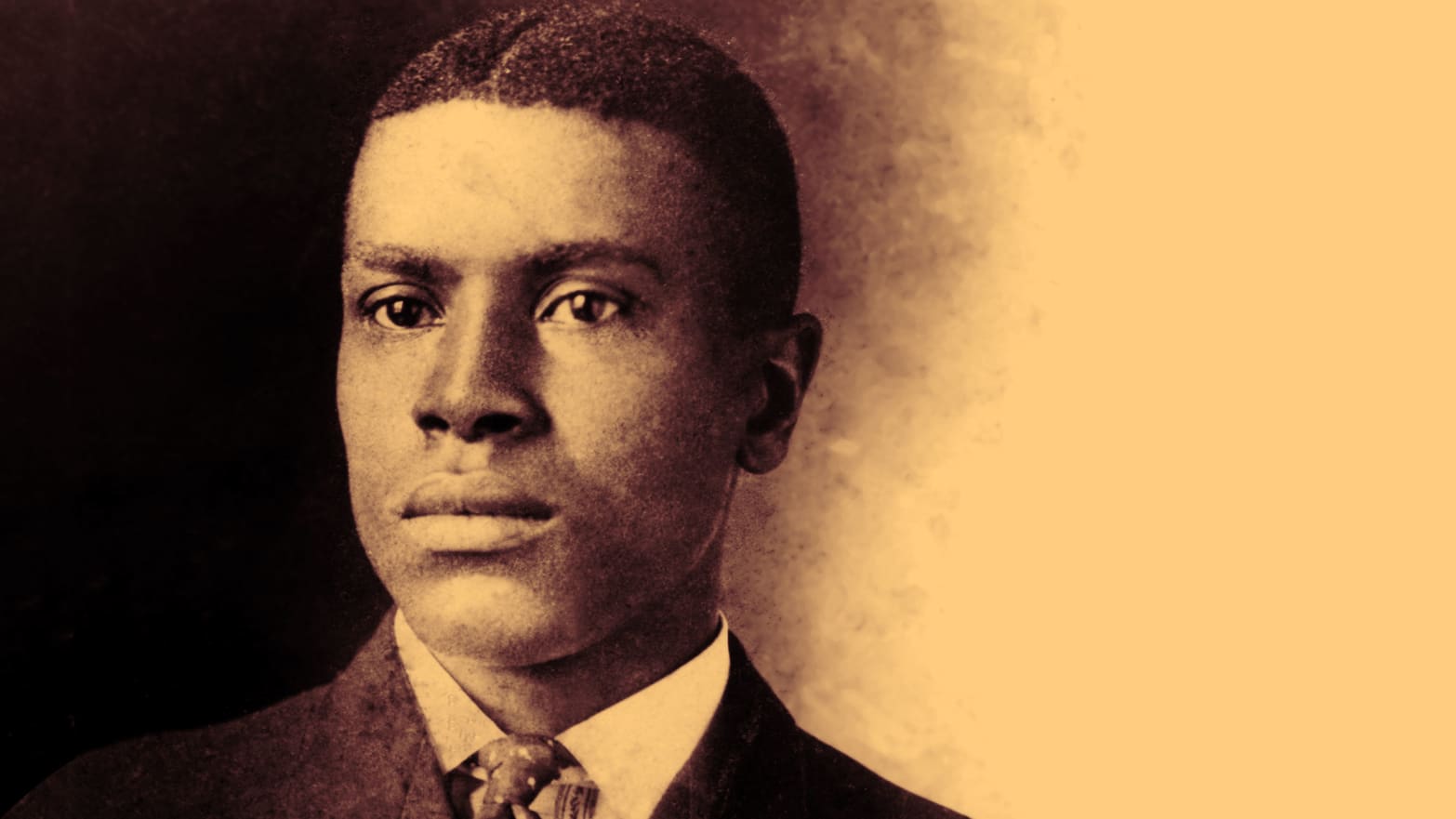

OSCAR MICHEAUX

OSCAR MICHEAUX

Oscar Micheaux wasn’t without controversy, however. More than once, he was harshly criticized by black elites regarding representation, which is a hot button topic even today. One relevant example is ‘Body and Soul’ (1925), which irked the African American press for its treatment of a false preacher, splendidly portrayed by Paul Robeson. Black American stereotyping was already bad enough, they said, thus seeing no need to further engage in such deliberate debasing. But Micheaux counterpunched with a simple argument: realism was the key to the progress of the race.

‘I am too much imbued with the spirit of Booker T. Washington to engraft false virtues upon ourselves, to make ourselves that which we are not. Nothing could be a greater blow to our own progress. The recognition of our true situation will react in itself as a stimulus for self-advancement’, the luminary director once said.

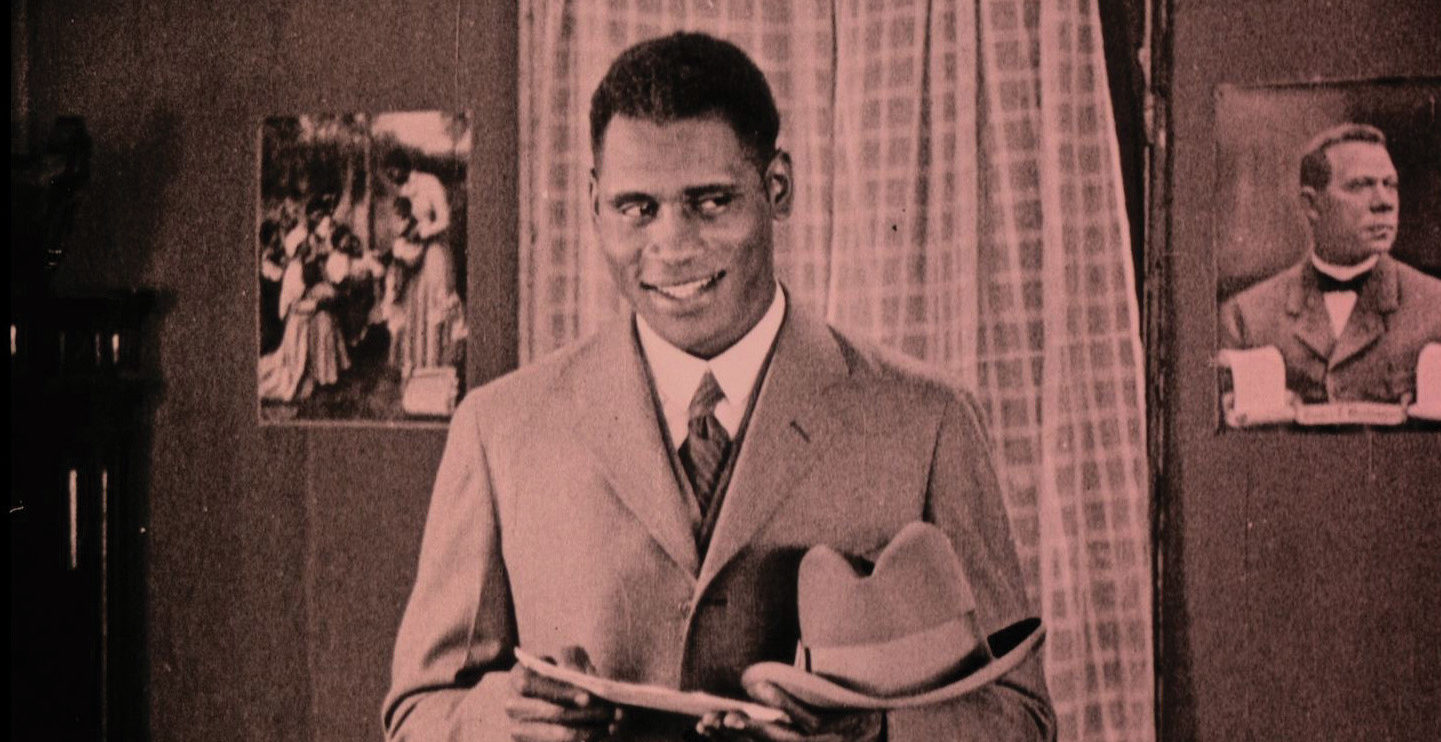

‘BODY AND SOUL’ (1925), ©MICHEAUX FILM

‘BODY AND SOUL’ (1925), ©MICHEAUX FILM

Of Interracial Film Production Companies

Self-representation was rare in the writing and production of Black American films in the early 1900s. Most companies behind such titles were usually interracial ventures. Only a handful were fully black-owned and operated. Nevertheless, it is not easy at all to accurately observe the difference between how White Americans and Black Americans treated racial themes. Both types of productions offer a compelling impression of how cinema and storytelling were perceived by black and white people in the United States, but it would be a mistake to assume that films made by white-owned companies were more compromised than those authored by African American filmmakers.

Most of the interracially-produced ‘race films’ are best accepted as collaborations between writers, directors, producers, performers, camera operators and editors of different backgrounds that worked together to deliver cinematic experiences specifically for Black American audiences. Their goal was to produce stories of black life that went against the salacious and downright vicious mainstream movies. One such noteworthy oeuvre is white filmmaker Richard E. Norman’s ‘The Flying Ace’ (1926), its story exclusively set in the African American world. Focused on a returning war pilot and his rival for the love of the local railroad stationmaster’s daughter and modelled after famed Black American aviator Bessie Coleman, ‘The Flying Ace’ weaves its fictional narrative with the real heroism of African Americans that was already familiar to its desired audience.

‘THE FLYING ACE’ (1926), ©NORMAN FILM MANUFACTURING COMPANY

‘THE FLYING ACE’ (1926), ©NORMAN FILM MANUFACTURING COMPANY

Of Early Black American Stars

The Criterion Channel collection boasts an impressive array of black cinema, revealing the exceptional diversity of the roles that Black Americans undertook within the film industry—both in front of and behind the camera. It’s truly a pleasure to mention silver screen legends like Charles Sidney Gilpin, Lorenzo Tucker, Evelyn Preer, Flournoy Miller, and Paul Robeson, among many others.

Charles Gilpin was best known for his stage work, but ‘Ten Nights in a Barroom’ (1926) raised him to nationwide stardom in the African American community. Lorenzo Tucker is remembered to this day as ‘The Black Valentino’, admired for his dark and athletic complexion, and a darling of African American films—especially Oscar Micheaux’s, of which he did 18.

‘The First Lady of the Screen’ was Evelyn Preer’s nickname, and for good reason. She was a stage and film actress, as well as a jazz and blues singer who captivated the American public from the 1910s well into the 1930s. By most historical standards, Ms Preer was the first black actress to earn popularity and celebrity, appearing in pivotal movies and stage productions, including ‘The Chip Woman’s Fortune’ by Willis Richardson, widely regarded as the first dramatic play by an African American playwright to be produced on Broadway.

EVELYN PREER IN ‘WITHIN OUR GATES’ (1920), ©MICHEAUX BOOK & FILM COMPANY

EVELYN PREER IN ‘WITHIN OUR GATES’ (1920), ©MICHEAUX BOOK & FILM COMPANY

Flournoy Miller was one of the seminal figures of Black Broadway, earning a Tony nod for his performances, renowned as a vaudevillian entertainer alongside Aubrey Lyles and as Slim Perkins in ‘The Bronze Buckaroo’ (1939). But when it comes to astonishing greatness, one need to look no further than the magnificent Paul Robeson, a bass baritone with exquisite thespian talents who turned Eugene O’Neill’s plays into otherworldly masterpieces. Of course, given the difficult times he was born into, Mr Robeson became not only famous for his cinematic contributions but also notorious for his Cold-War-era advocacy for human rights. The latter, sadly expected, led to the eventual ruin of his illustrious career, though he remains today an everlasting symbol of Black American pride and consciousness.

I have to mention Francine Everett, dubbed ‘the most beautiful woman in Harlem’ and one of the most beautiful black actresses to grace the silver screen with her hypnotic presence. Ms Everett was one of the more frequent credits in race films, preferred by black audiences to Lena Horne and Dorothy Dandridge because she never transformed her screen persona into something more aloof, designed to please white audiences. In fact, she insisted on keeping her warmth and down-to-earth nature best evoked in Spencer Williams’s ‘Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A.’ (1946).

FRANCINE EVERETT IN ‘DIRTY GERTIE FROM HARLEM U.S.A.’ (1946), ©SACK AMUSEMENT ENTERPRISES

FRANCINE EVERETT IN ‘DIRTY GERTIE FROM HARLEM U.S.A.’ (1946), ©SACK AMUSEMENT ENTERPRISES

Let us not forget Herb Jeffries, either, who once sang with Duke Ellington’s orchestra and can be easily admired as a singing cowboy in several black-cast westerns for Richard C. Kahn, a white producer—‘The Bronze Buckaroo’ pops up again for this. And the Moses sisters, first noticed as Cotton Club chorus dancers, should also be applauded. Lucia Lynn Moses can be seen in ‘The Scar of Shame’ (1929), produced by the Colored Players Film Corporation of Philadelphia, and Ethel Moses appears in Oscar Micheaux’s ‘Birthright’ (1938).

Of Early Black American Filmmakers

There were restrictions that made filmmaking more challenging for black artists in the Jim Crow era. Few businessmen were willing to invest in black-made films—even the interracial endeavours had their share of financial hiccups due to racism. One consequence of restricted budgets was that filmmakers would frequently shoot outside the studios and turned to nonprofessional actors alongside the professional leads. The results are mesmerizing today because we’re given shots of real streets, shops, churchgoers, and many other elements of Black American communities.

Going back to Oscar Micheaux’s ‘Body and Soul’, where Paul Robeson’s false preacher delivers a passionate sermon to a congregation filmed on set, the director adds snippets of real churchgoers in the rural landscape, appealing directly to the people it aims to represent. ‘The Blood of Jesus’ (1941) by Spencer Williams may be a fiction film, but its narrative is built around elongated scenes of religious practices performed by the very real Reverend R.L. Robertson and the Heavenly Choir in the company of members of the Texas community in which the story was shot.

‘THE BLOOD OF JESUS’ (1941), ©AMEGRO FILMS

‘THE BLOOD OF JESUS’ (1941), ©AMEGRO FILMS

Delving deeper into the aspect of realism presented by race films, one will find home movies of Reverend Solomon Sir Jones included in the ‘Pioneers of African American Cinema’ collection. The Reverend was a Baptist preacher of Oklahoma who documented black communities across the United States from 1924 to 1928, painting them as bold clusters of self-determination. Other unique documents of Black Cinema include films by James and Eloyce Gist, which are fictionalized biblical parables used for demonstration during religious sermons. ‘Hell-Bound Train’ of 1930 is one such production.

Zora Neale Hurston’s contributions are an integral part of the Criterion selection, as her anthropological fieldwork non-fiction movies offer splendid images of late ‘20s’ Alabama and Florida, and of the Gullah people from a Sea Island community in South Carolina, dated about two decades later. The latter can be connected to Julie Dash’s ‘Daughters of the Dust’ (1991).

STILL FROM COMMANDMENT KEEPER CHURCH, BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA (1940), BY ZORA NEALE HURSTON

STILL FROM COMMANDMENT KEEPER CHURCH, BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA (1940), BY ZORA NEALE HURSTON

Of Stories Lost in History

Unfortunately, one too many gems of Black American cinema are lost. Bits and pieces can be found in archives and the aforementioned Pioneers collection, including a few surviving fragments of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company’s last film. Lincoln Motion Picture Company was one of the first race film producers, owned by George and Noble Johnson. You will remember the latter as the earliest of black movie stars and a renowned character actor in Hollywood.

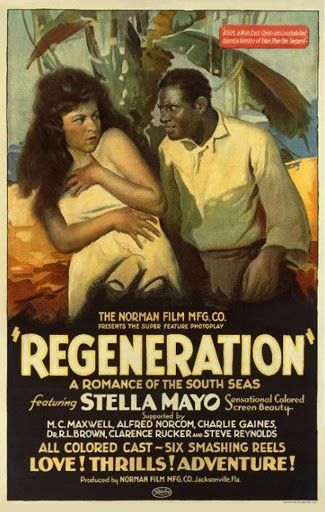

Four minutes of ‘By Right of Birth’ (1921) remain today, but each frame is incredible, the whole piece filled with comedy, romance, action, and intrigue—not an easy feat to accomplish on film in a medium that young. Another endangered work is ‘Regeneration’ (1923) by Richard E. Norman, a high seas thriller whose nitrate decomposition is a heart-breaking reminder of what became of most silent films. Mr Norman is fondly remembered as one of the few white filmmakers who devoted his career to black-oriented movies and hired black casts for his productions. Survival rates are even lower for Black American films, for which fewer copies were made.

Ultimately, none of the films signed by the earliest black filmmakers of the 1910s have made it. Works by George W. Broome, William Foster, Hunter C. Haynes, and Peter P. Jones are forever lost, which makes what we do have all the more precious and important, not only for Black American culture but for our entire civilization, where cinema is concerned.

POSTER FOR ‘REGENERATION’ (1923), ©NORMAN FILM MANUFACTURING COMPANY

POSTER FOR ‘REGENERATION’ (1923), ©NORMAN FILM MANUFACTURING COMPANY

Of Risky and Complex Racialized Performances

Early Black American cinema, both black- and white-produced, was not without its blunders and controversial scenes. Take ‘Two Knights of Vaudeville’ (1915), for example, a comedy produced by the white-owned Historical Feature Film Company from Chicago that shamelessly flaunts racist tropes. Oddly enough, it’s also a surprisingly interesting depiction of the vaudevillian stage and an imagined all-black performance space. With comedy especially prone to criticism, it was no surprise that the Chicago Defender railed against the producers for their ‘buffoonish portrayals’. The paper went even further and proclaimed that they ‘want clean Race pictures or none at all.’

Ebony Film Co. were also heavily criticized by the Black American press for some of their general-release comedies—good examples being ‘Mercy, the Mummy Mumbled’ (1918) and ‘A Reckless Rover’ (1918), despite having respected African American businessman Luther J. Pollard at the helm. Once again, the Chicago Defender warned their readers: ‘Keep your money in your pocket and save that dime as well as your self-respect.’

Oscar Micheaux does not evade critique, either. One might have trouble to reconcile some of his ‘30s works with his noble portrait as a ‘race man’. After all, in ‘The Darktown Revue’ (1931), one of his first sound projects, the filmmaker incorporates black actors in blackface makeup. To contemporary viewers, this and ‘Ten Minutes to Live’ (1932) may be less palatable. Yet such snippets of Black American cinema give us a broad picture of the many tensions that persisted in the industry at the time. Micheaux’s motivations are not easily discerned, especially since films like ‘The Darktown Revue’ function on now-decrepit and compromised aesthetics.

‘THE DARKTOWN REVUE’ (1931), ©MICHEAUX FILM

‘THE DARKTOWN REVUE’ (1931), ©MICHEAUX FILM

Early African American film history remains plagued by unknowns. There is still so much for us to rediscover, to study, and to better understand, not only about the movies themselves but about their cast members and production crews, too. Alas, race films’ decline occurred in the late 1940s, mostly because of the increasingly racist policies enforced by the American government, leading to frustrating segregationist measures that almost killed Black Cinema. Fortunately, 1964 brought forth the Civil Rights Act. With it came fundamental changes, but without these earlier filmmakers, none of the modern productions would be what they are today.

Race films continue to inform black filmmaking, with the collective experiences of its audiences at its very core.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.