Of the directors who carved their place into the history of cinema, Guillermo del Toro stands out as an inventive visionary, a master of the whimsical dread, and a father of monsters and curious creatures. His films are different from most in the fantasy genre, the result of multiple influences that have shaped the Mexican director over the years. Mr del Toro’s Lovecraftian accents and fatherly love for horror tale monsters are but two of the elements that have defined his cinematic art since before he even picked up his father’s Super 8 to film his own version of ‘Planet of the Apes’ (1968).

Starting with ‘Cronos’ (1993), his first feature-length movie, and going through ‘The Devil’s Backbone’ (2001), ‘Pan’s Labyrinth’ (2006), to his more recent ‘Pacific Rim’ (2013), ‘Crimson Peak’ (2015), and ‘The Shape of Water’ (2017), it is easy to spot the director’s love of everything weird and spine-tingling. But if one wishes to truly understand Guillermo del Toro, one must first journey from his Guadalajara childhood all the way into Bleak House, his beloved museum of creepy, fantastic and otherworldly. There is plenty to unpack.

‘PAN’S LABYRINTH’ (2006), ©ESTUDIOS PICASSO/WILD BUNCH

‘PAN’S LABYRINTH’ (2006), ©ESTUDIOS PICASSO/WILD BUNCH

Monsters, Cinema, Death

These are the three things that best describe del Toro’s imagination and its cinematic manifestations. In ‘At Home with Monsters: Inside His Films, Notebooks, and Collections’, the companion book to the eponymous Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibit from 2016, he writes: ‘When I was a child—a very young child—a hairline fracture became evident in my soul. I felt growingly disfranchised, puzzled, and at odds with the adult world. It was made up of rules and notions that were both alien and unexplained, and life came to feel like a rigged game. It was entirely composed of lies.’

As adults, we lie about almost everything—how much money we make, how tall we are, what our natural hair colour is, what our dreams are made of. We lie to others and we lie to ourselves, and yet we frown upon fantasy and consider it childish. It was this sense of creative injustice that fuelled del Toro’s love of stories ever since he was a little boy.

‘THE DEVIL’S BACKBONE’ (2001), ©EL DESEO/TEQUILA GANG

‘THE DEVIL’S BACKBONE’ (2001), ©EL DESEO/TEQUILA GANG

Born in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 1964, Guillermo del Toro was mostly raised by his Catholic grandmother. His childhood, which he frequently revisits in his films, was marred by repressed Catholicism and bullying classmates. It was saved by books, movies, and horror comics. He started drawing at a young age, much like the orphaned Jaime in ‘The Devil’s Backbone’, and he hasn’t stopped since. His notebooks are standalone works of art that have nurtured his imagination and have given birth to memorable monsters. It’s where he records ideas, lines of dialogue, various lists and images—food for his films, he’ll say.

His love of cinema comes from this period, too. He devoured pretty much any B-movie and horror film that he could find, as well as the more classical works from Alfred Hitchcock and Luis Buñuel. He loved the Universal monster movies that made it to Mexican television, and he voraciously consumed fan magazines. Del Toro taught himself English in order to understand the slang and puns of American periodicals like ‘Famous Monsters of Filmland’.

A YOUNG GUILLERMO DEL TORO WITH RON PERLMAN

A YOUNG GUILLERMO DEL TORO WITH RON PERLMAN

In his teenage years, he worked as a projectionist for his local cinema club, watching several movies every week and passionately discussing them with other cinephiles. It was Luis Buñuel’s ‘Los Olvidados’ (1950) that proved the art value of cinema to a young del Toro, his love of film only matched by his love of comic books. Moebius (Jean Giraud), Frank Frazetta and Richard Corben count as his earlier influences in illustration. This later transpired into adulthood through his work on two Hellboy films with Mike Mignola.

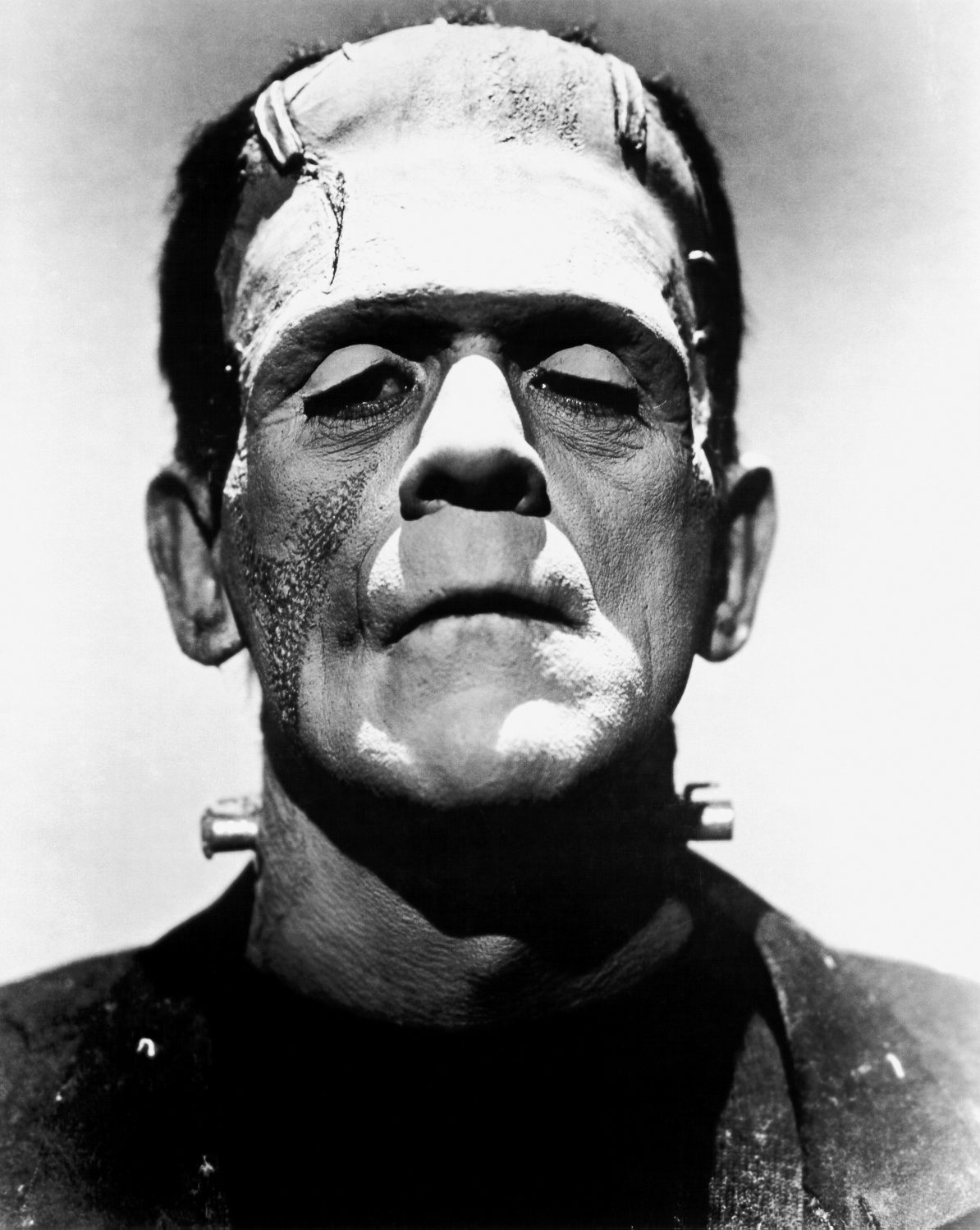

There are a couple of other elements that were absorbed into his cinematic work. One came in the form of James Whale’s ‘Frankenstein’ (1931), as del Toro identified with the outsider status of Boris Karloff’s confused and abused monster. He found in Frankenstein an eloquent analogy to his directorial approach, since his movies are collages of used, discarded and different source materials that were given new life and purpose.

BORIS KARLOFF AS ‘FRANKENSTEIN’ (1931)

BORIS KARLOFF AS ‘FRANKENSTEIN’ (1931)

Growing up in ‘60s and ‘70s Guadalajara, Guillermo del Toro had several disturbing confrontations with death, the second other seminal element. He saw corpses in the streets more than once, as well as in a morgue and in the catacombs beneath the local church. He was pummelled by the notion of the original sin and even subjected to the horrors of exorcism because of his grandmother, in a useless attempt to obliterate his obvious love of monsters and fantasy. Today, the director is an outspoken critic of institutional Catholicism, saying: ‘The fantastic is the only tool we have nowadays to explain spirituality to a generation that refuses to believe in dogma or religion.’

In his films, the prospect of immortality that is promised in Catholic doctrines as a reward for obeying the church is translated into an arrogant desire that ultimately leads to the self-destruction of those who chase such wild dreams. In the end and despite the array of both wonderful and terrible experiences, del Toro walked into adulthood with a clear sense of belonging in the world of horror fantasy. ‘I really think I was born to exist in the genre’, he says. ‘I adore it. I embrace it. I enshrine it. I don’t look upon it or frown upon it in a way that a lot of directors do. For me, it’s not a steppingstone, it’s a cathedral.’

ANGEL OF DEATH SCULPTURE, INSPIRED BY ‘HELLBOY II: THE GOLDEN ARMY’ (2008)

ANGEL OF DEATH SCULPTURE, INSPIRED BY ‘HELLBOY II: THE GOLDEN ARMY’ (2008)

Themes, Influences, Inspiration

In his films, del Toro often asks an interesting question: what happens when two opposing frameworks for understanding the world confront one another? Different protagonists fight against forces of disorder, struggling in their own way. Some refuse to admit the futility of this war, while others learn to accept chaos, emerging victoriously with greater powers of their own.

Colour plays an essential role in the way he communicates his cinematic vision. In an interview with Keith McDonald and Roger Clark, Guillermo del Toro points to Federico Fellini as a key influence. The Italian director once said: ‘When I transitioned into colour, I made a point of having the colour tell the story.’ Following in his footsteps, Mr del Toro applied similar purpose to colour in his movies. For example, he patterned ‘Cronos’ with the colours of the alchemical process—black, red, white, and gold, with an addition of water and fire elements into the overall canvas.

‘Colour gives you the key of the film in the same way that some songs are better in one key than another, and [the keys] define the genre of the song’, the director said.

‘CRONOS’ (1993), ©CNCAIMC/GRUPO DEL TORO

‘CRONOS’ (1993), ©CNCAIMC/GRUPO DEL TORO

Many of del Toro’s creations feature children as central characters. They are witnesses, victims, or agents. Frequently, they are able to perceive alternate realities, producing unfiltered emotions in a way that adults cannot. Most importantly, the director refuses to shield his young protagonists from fear, abandonment, harm, or death. Well read in folklore and fable literature, del Toro insists that children cannot be protected, that they are vulnerable—and fairy tales often prove it. His films will sometimes reference classic illustrated editions of children’s stories from the 19th century, with one instance being Ophelia in ‘Pan’s Labyrinth’, who is dressed similarly to Alice in Wonderland as rendered by Arthur Rackham.

‘PAN’S LABYRINTH’ (2006), ©ESTUDIOS PICASSO/WILD BUNCH

‘PAN’S LABYRINTH’ (2006), ©ESTUDIOS PICASSO/WILD BUNCH

Victoriana is a copious source of inspiration for Guillermo del Toro. The Victorian Period, loosely considered to cover the Romantic era and the Edwardian age, is thoroughly represented by Charles Dickens in the director’s mind. He named his beloved Los Angeles personal residence/museum of curiosities after the English writer’s ‘Bleak House’ novel. Houses in both Victorian novels and his films are endowed with pasts as complicated and unresolved as their inhabitants. Mr Dickens’s memorable melange of realism and fantasy is but one of his many influences that can be found across the whole span of del Toro’s work.

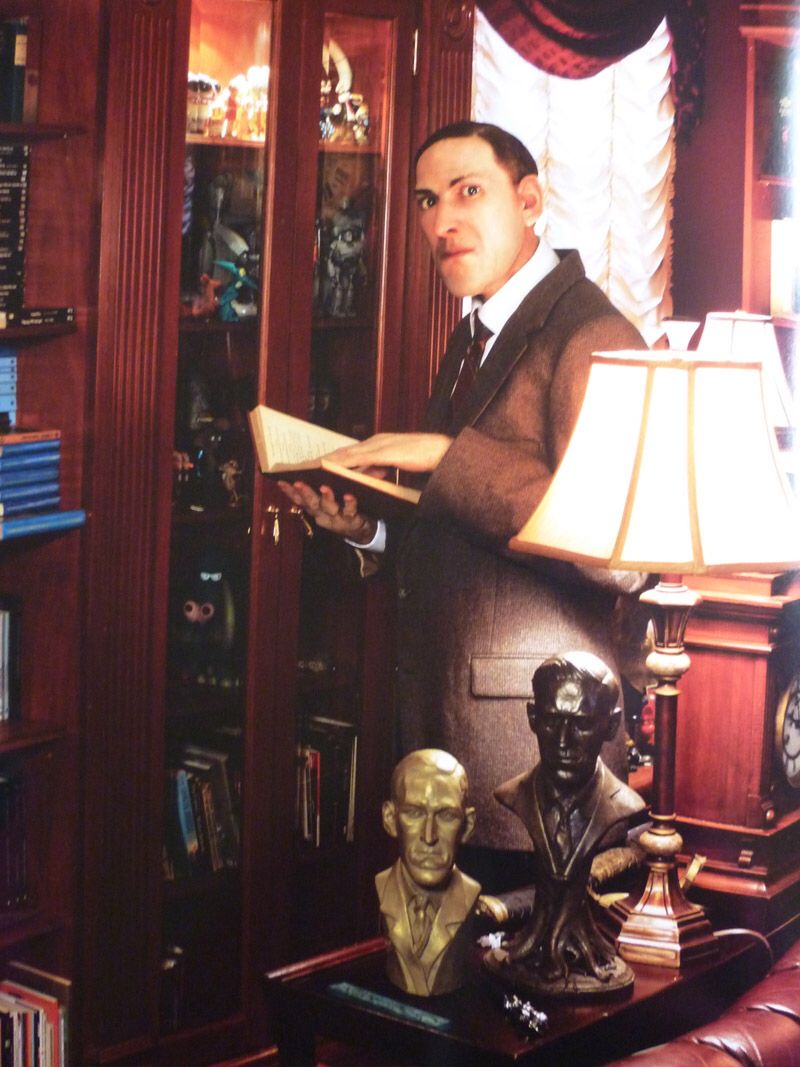

INSIDE BLEAK HOUSE, ©JOSHUA WHITE/JWPPICTURES.COM/LACMA

INSIDE BLEAK HOUSE, ©JOSHUA WHITE/JWPPICTURES.COM/LACMA

Filled with puzzles, talismanic items, secret keys and quests for forbidden knowledge, his films draw their strength from a vast collection on the topics of magic, witchcraft, and the occult. Many of his characters are scientists, whom he considers ‘contemporary successors to the monks and alchemists who explored the boundaries between the holy and the unholy’—this is brilliantly exemplified by the fourteenth-century alchemist who kickstarts the present-day action in ‘Cronos’ with his scarab-like device that gives immortality along with a thirst for blood.

Guillermo del Toro also cites H.P. Lovecraft as one of the key influences in his creative life, whose work is foundational to both the horror and science fiction genres. The American writer’s vivid expressions of madness, transformation and monstrosity have been the source of inspiration and frustration to numerous directors, and Mr del Toro is no exception. There is a smidge of Lovecraft in almost each of his films. ‘Lovecraft did something very interesting with the traditional Gothic and horror narrative. He brought a scientific and existential point of view to it’, says del Toro in his exhibition book.

LIFE-SIZE STATUE OF H.P. LOVECRAFT IN BLEAK HOUSE, ©CHRIS MOORE

LIFE-SIZE STATUE OF H.P. LOVECRAFT IN BLEAK HOUSE, ©CHRIS MOORE

However, it’s the freaks and the monsters that are the true building blocks of his films. To him, they’re all fascinating—the movie ones as much as those found in nature, literature, in myths and in art. ‘It’s either tragedy or superiority that makes a good monster’, del Toro notes. These creatures are beautiful and heroic in their individuality, and they are also mirrors of society’s hypocrisy. According to the director, ‘the conventional standards of perfection that surround us in commercial culture are corrosive, demonizing the imperfections that characterize us all.’

While he usually identifies with the tragic type of monster, Mr del Toro is equally skilled at creating truly horrifying and indestructible fiends, too. The creation process begins with him thinking of the monster as a character, not merely a mixture of terrifying elements or a force that impacts the plot in one way or another. The creature must be visually convincing from every single point of view. Most importantly, his monsters strive to be instantly recognizable, impossible to forget, and downright iconic.

Many of them have insect-like features and behaviours. They’re designed for survival, usually in an elegant manner, but they still manage to cause an emotional reaction of fear and revulsion in most people.

‘PACIFIC RIM’ (2013), ©WARNER BROS.

‘PACIFIC RIM’ (2013), ©WARNER BROS.

Bleak House

‘I built a house made of books, art, film, and monsters. A house of many stories: dark and stormy stories. A house with secret passages and sliding bookshelves and portraits that follow you as you walk by. I dreamt it all those years ago, alone in the dark, but I only got to build it at age forty-four’, Guillermo del Toro speaks fondly of his home. It inspired an extraordinary exhibition that could be admired at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Art Gallery of Ontario in recent years. Parts of his collections were taken from Bleak House and put on display for the whole world to see the creepy and wondrous things that make his mind click.

Bleak House isn’t just Guillermo del Toro’s residence. It is a cornucopia of objects, notebooks, maquettes, drawings, paintings, film concept art, and artefacts—assemblies of film memorabilia, art, and literature which he considers to be essential sources of inspiration. Bleak House feeds his very soul. These collections grow organically, not chaotically. Del Toro is precise and personally involved in the arrangement and curation of every object. There is purpose in this dedication, as Bleak House is crucial to his working process.

GUILLERMO DEL TORO IN BLEAK HOUSE WITH A LIFE-SIZE STATUE OF SCHLITZIE AND H.R. GIGER ORIGINAL ARTWORK, ©JOSH WHITE/JWPICTURES.COM

GUILLERMO DEL TORO IN BLEAK HOUSE WITH A LIFE-SIZE STATUE OF SCHLITZIE AND H.R. GIGER ORIGINAL ARTWORK, ©JOSH WHITE/JWPICTURES.COM

Life-size sculptures of Hans and Schlitzie from ‘Freaks’ (1932), Edgar Allan Poe, and H.P. Lovecraft are among the more memorable ‘residents’, along with a plethora of monster figurines, and portraits and/or miniatures of Forrest Ackerman, celebrated magazine editor and literary agent who once represented Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov, giants of science fiction; makeup effects legend Dick Smith, whom the director studied under; and revered stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen.

The house is crafted into thematic sections, and there is an enormous head of Frankenstein’s monster adorning the foyer. A history section includes busts of magicians Harry Houdini, Howard Thurston, Chung Ling Soo, and Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin. In the rain room, there is a life-size sculpture of Boris Karloff in chair as he’s transformed into Frankenstein’s monster by renowned horror makeup artist Jack Pierce. Linda Blair as Regan MacNeil from ‘The Exorcist’ (1973) is also present.

THE FOYER OF BLEAK HOUSE, ©JOSH WHITE/JWPICTURES.COM

THE FOYER OF BLEAK HOUSE, ©JOSH WHITE/JWPICTURES.COM

One will find thousands of books, as well, of both fiction and non-fiction. Among his most prized possessions, Mr del Toro mentions the entire collection of ‘Man, Myth & Magic: An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of the Supernatural’, a twenty-four volume set that was published in 1970, and which the director loved to pore over as a child. Alas, Bleak House is any fantasy and horror aficionado’s dream home.

Into the Future

Guillermo del Toro has recently finished penning the script for Disney’s upcoming ‘Pinocchio’ (2021) and ‘Nightmare Alley’ (2021), along with a sequel to ‘Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark’ (2019). Mr del Toro has also found a certain joy in animation with ‘Trollhunters: Tales of Arcadia’ (2016-2018), and he is currently moving ahead with ‘Wizards’, the third instalment of the Arcadia series.

For almost a decade, the director has struggled with a repeatedly cancelled adaptation of Lovecraft’s novella, ‘At the Mountains of Madness’, originally published in 1936. Refusing to surrender and constantly surrounded by portraits and busts of the writer at Bleak House, del Toro continues to plot and work on a way to bring this particular story to the silver screen.

GUILLERMO DEL TORO IN BLEAK HOUSE NEXT TO A LIFE-SIZE STATUE OF EDGAR ALLAN POE, ©JOSH WHITE/JWPICTURES.COM

GUILLERMO DEL TORO IN BLEAK HOUSE NEXT TO A LIFE-SIZE STATUE OF EDGAR ALLAN POE, ©JOSH WHITE/JWPICTURES.COM

Refusing distinctions between high and low culture, Guillermo del Toro is utterly unapologetic about what moves him in this life. Having found inspiration in the comics of Bernie Wrightson and Alan Moore, in TV shows like ‘The Twilight Zone’ (1959-1964) and ‘The Outer Limits’ (1963-1965), in the moving images of Federico Fellini and James Whale, and in the art of Francisco Goya and James Ensor, he uses his influences as instruments for crafting deeply philosophical themes.

Like an alchemist, del Toro takes these bits and pieces and transmutes them into incredible film worlds where monsters and innocents are given new purpose, driven by the very mystery and uncertainty that defines the human condition.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.