It seems like ages ago that the film industry came to life. Discussing cinema today wouldn’t be possible without the decades of technological and artistic progress dating back to the end of the 19th century. Sometimes, we seem to forget exactly how fortunate we are that this medium exists, and that we are able to create immortal pieces of art through it. With that in mind, and solely for the purpose of a most absorbing and instructive experience, we’ve decided to sift through the dusty pages of cinematic history and take a trip down celluloid memory lane.

The first decade of cinema history pretty much begins in 1895. Up to that point, mankind’s main forms of entertainment revolved around literature, theatre, the visual arts (painting and ballet, for the most part), musical concertos, and storytelling. But the moving image as an art form was difficult to establish, mainly due to technical insufficiencies. Apart from the magic lantern phantasmagoria shows of the 18th century and the camera obscura, we didn’t get to the seedlings of cinema until the development of chronophotography.

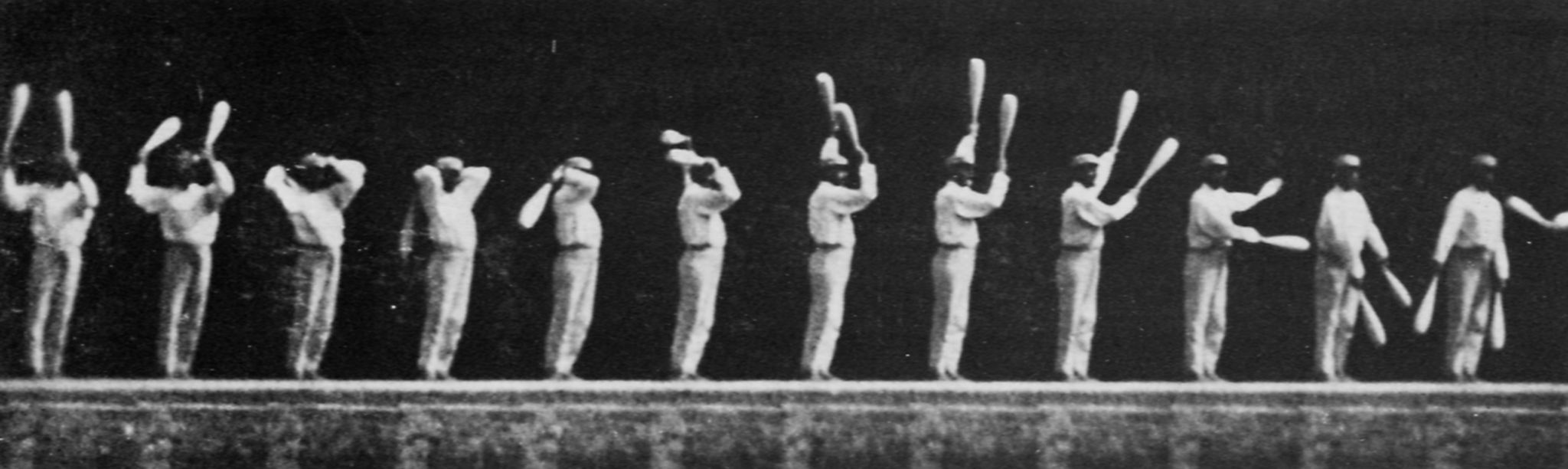

This was an antique photographic technique of the Victorian era, which captured movement in several frames of print. These, in turn, could be subsequently arranged either like animation boards or layered into a single frame. It started with Eadward Muybridge’s studies of the motion of animals and humans, swiftly followed by other esteemed chronophotographers such as Étienne Jules Marey, Ottomar Anschütz, and Georges Demenÿ. These efforts led to viewing moving images through zoetropes, and later to animating the same sequences into short films.

CHRONOPHOTOGRAPHY ON A FIXED DISK WITH A ROTATING MIRROR, 1888, BY ÉTIENNE JULES MAREY

CHRONOPHOTOGRAPHY ON A FIXED DISK WITH A ROTATING MIRROR, 1888, BY ÉTIENNE JULES MAREY

The real breakthrough came through the invention and the progression of the camera, then merely fastened to tripods. Once the aspiring filmmakers had this first device, they were able to shoot and screen their earliest work.

1895: The Film Luminaries Who Made History

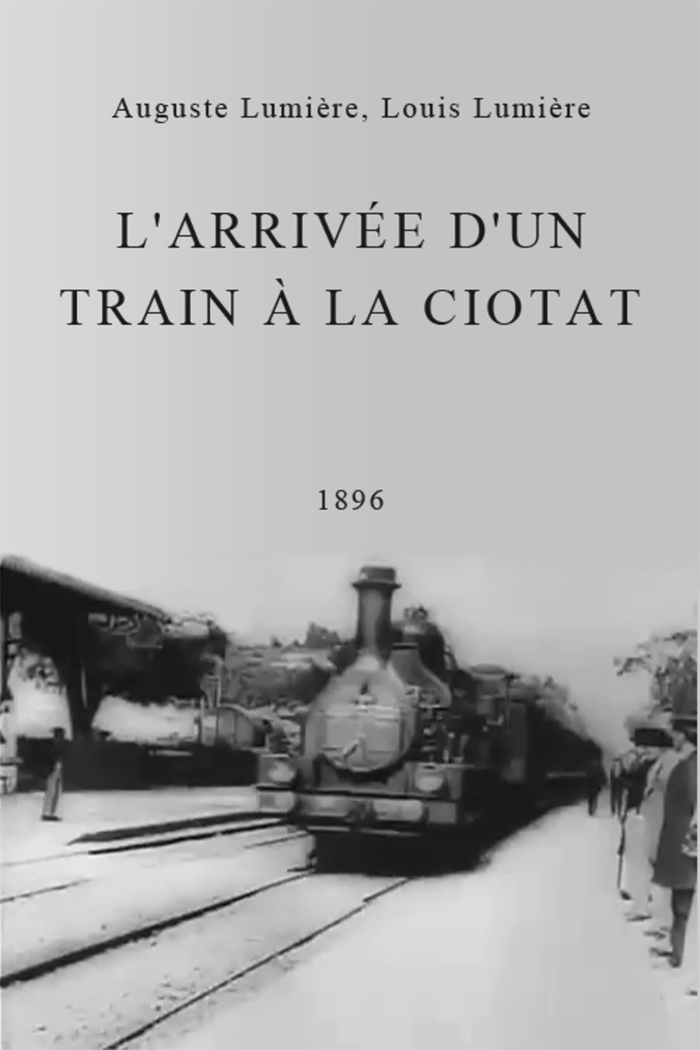

It all started with the Lumière brothers, who gave us the first camera movements by mounting the camera on a moving vehicle. ‘Arrival of a Train at Ciotat Station’ was basically a scene from the back of a train, and it was screened on December 28th, 1895 for paying customers. This marked the birth of cinema as entertainment and of motion-picture exhibition as a business.

ARRIVAL OF A TRAIN AT LA CIOTAT STATION (1895), ©LUMIÉRE

ARRIVAL OF A TRAIN AT LA CIOTAT STATION (1895), ©LUMIÉRE

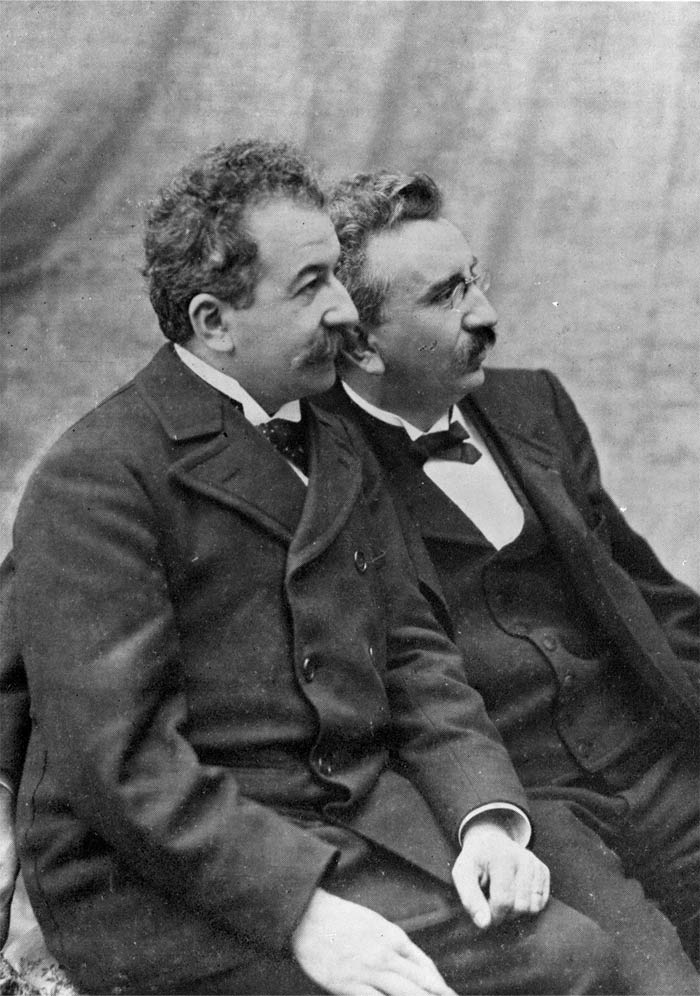

Auguste and Louis Lumière were manufacturers of photographic products from Lyon, France, and they were responsible for devising the patented apparatus capable of both photographing motion on film stock and projecting its results onto a screen. Prior to their December showing, they’d managed to introduce their ‘Cinématographe’ to Parisian industrialists and scientists, playing the one film they’d shot at the time: ‘Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory’. Later, they were able to produce more ‘views’, as they called them, further arousing interest among photography specialists.

THE BROTHERS LUMIÉRE

THE BROTHERS LUMIÉRE

But it was ‘Arrival of a Train at Ciotat Station’ that was a truly seminal moment, as they introduced the new wonder machine to the general public. The premiere took place in a room called the ‘Salon Indien’ in the basement of the Grand Café on Boulevard des Capucines, close to the Opéra, which could seat about a hundred people. There were four evening shows on that historic date in December 1895, and they brought in a mere 35 francs—which didn’t cover the brothers’ expenses, but business rapidly picked up afterwards.

Long lines of eager spectators stretched across the boulevard, and the success drove the Lumière brothers to rent a new and larger venue in April 1896. They called it ‘Cinéma Lumière’.

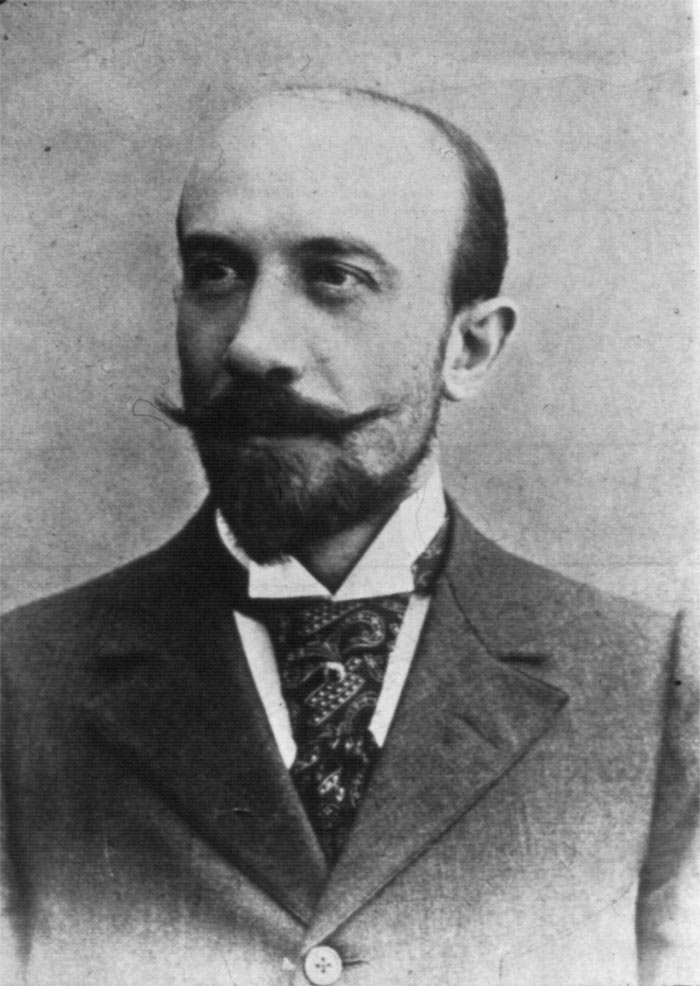

1896: Stop Motion by Mistake

An accident was at the origin of the development of the first special effects in cinema, and Georges Méliès was responsible for this amazing breakthrough. His rudimentary first camera was prone to jamming, a defect which, according to Mr Méliès, ‘produced an unexpected effect one day when I was prosaically photographing the Place de l’Opéra. It took a minute to unblock the film and get the camera going again. During this minute, passers-by, buses, cars had changed their places, of course. In projecting the film, joined together again at the point where the break had occurred, I suddenly saw a Madeleine-Bastille bus change into a hearse, and men change into women’.

GEORGES MÉLIÈS

GEORGES MÉLIÈS

He had stumbled upon an exquisite and crucial trick which he quickly transformed into an intentional application with ‘Escamotage d’Une Dame au Thèâtre Robert Houdin (The Vanishing Lady)’ in October 1896. Discovering discontinuity within the apparent continuity of existence later paved the way for the enduring art of stop-motion animation, best represented by Willis O’Brien’s ‘The Lost World’ (1925), followed by ‘King Kong’ (1933), and by Ray Harryhausen’s ‘The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms’ (1953) and ‘Jason and the Argonauts’ (1963).

‘CORALINE’ (2009), ©FOCUS FEATURES/LAIKA ENTERTAINMENT

‘CORALINE’ (2009), ©FOCUS FEATURES/LAIKA ENTERTAINMENT

More recent examples of glorious stop motion animation films include ‘Coraline’ (2009) by Henry Selick and based on Neil Gaiman’s superb children’s book, ‘The Nightmare Before Christmas’ (1993) by Tim Burton, and ‘Isle of Dogs’ (2018) by Wes Anderson. In an era of CGI and special effects, stop motion animations have become veritable gems of cinematic passion.

1897: The World of Cinema Evolves

Three key events best defined this year. First, Robert William Paul developed the first rotating camera, which was able to take panning shots. He used it on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Panning describes the movement of one’s camera horizontally, either left to right or right to left, while its base is fixed on a certain point, and it’s an excellent method of establishing a sense of location within the story. D.W Griffith was one known adept of the panning shots, using them not only to provide visual information, but also to engage the audience in the complete environment of his films.

QUEEN VICTORIA’S DIAMOND JUBILEE (1897)

QUEEN VICTORIA’S DIAMOND JUBILEE (1897)

Second, Georges Méliès built one of the first film studios in May 1897. Conceived after the model of large still photography studios, it had three glass walls and a glass roof, and it was fitted with thin pieces of cotton fabric which could be stretched to diffuse the brighter sunlight. From that studio, Mr Méliès went on to produce, direct, and distribute more than 500 short films—most of them one-shot pieces completed in one take.

GEORGES MÉLIÈS’ STUDIO

GEORGES MÉLIÈS’ STUDIO

Third, the world’s first film archive was established, now considered an unfulfilled promise of historical awareness. Robert William Paul donated some of his films to the British Museum, hoping they would begin acquiring other reproductions of notable events in the form of moving pictures. The venerable institution didn’t really know what to do with the reels, however, and there never was a second donation. The first film archive was a mystery even for its owners. Denmark and Sweden tried the same later in the early 20th century, but there’s a certain pathos in the British precedent—there are hundreds of film archives all over the world today, yet their status is as fragile today as it was in 1897.

1901: Fatal Attraction, Beta Version

Films made before 1906 were generally categorized as ‘cinema of attractions’, a form of narration based on a single event of curious, extraordinary or otherwise remarkable nature—a train arriving in a station, the expression of a man suffering from indigestion, the grimaces of a playful child, and so on.

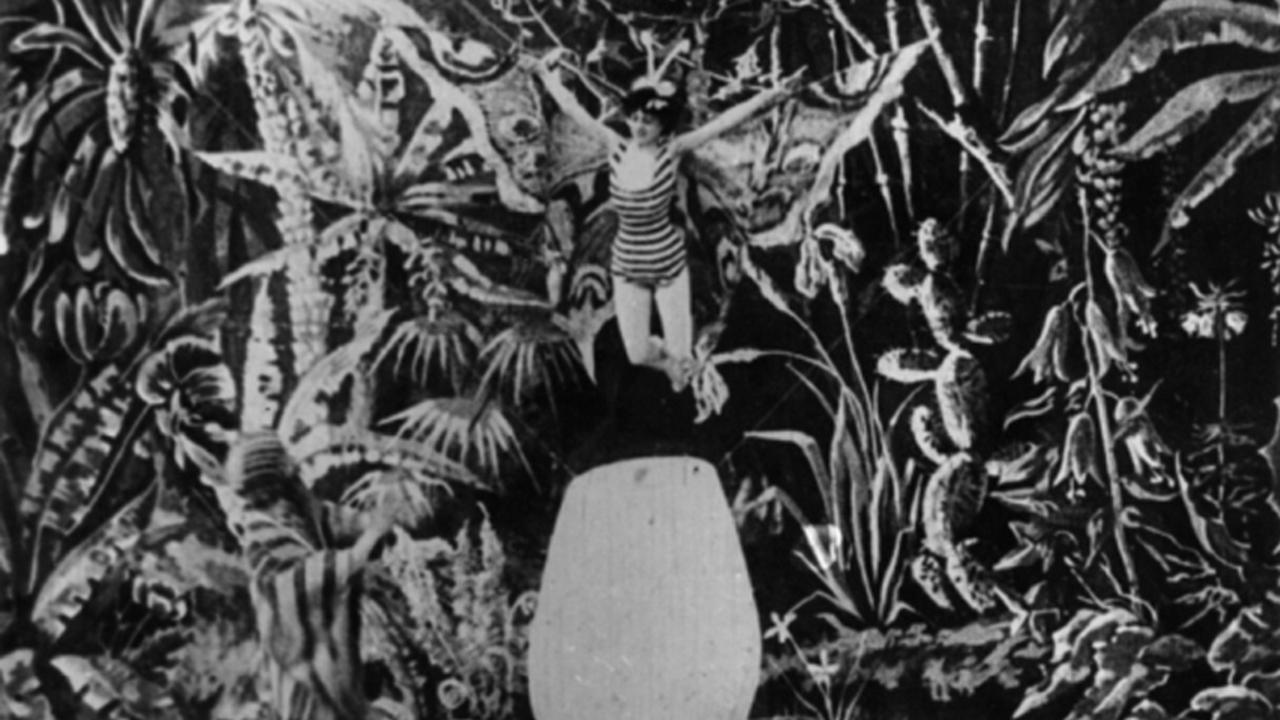

Georges Méliès’ ‘The Brahmin and the Butterfly’ is something else entirely. At first glance, it’s a two-minute scene, apparently made in a single shot, but there are in fact optical tricks that required in-camera editing. This wonderfully hand-coloured oriental garden of events depicts a Brahmin who summons a large caterpillar with his magic flute, then puts it into a cocoon, thus giving life to a gorgeous female butterfly.

‘THE BRAHMIN AND THE BUTTERLY’ (1901)

‘THE BRAHMIN AND THE BUTTERLY’ (1901)

Mesmerized by her beauty, the Brahmin wraps the butterfly in a striped cloth, and she turns into a ravishing Hindu princess. The man declares his unrequited love, only to see his courtship rebuffed, ending up with his head under her foot, then suddenly transformed into a crawling caterpillar similar to the one at the beginning of the story. Originally titled ‘La Chrysalide et le Papillon’, Méliès’ film is the most concise and cynical tale of ‘fatal attraction’ or ‘amor fou’. It’s the first of its kind, and possibly also the meanest.

1903: American Cinema Takes Centre Stage

The early 20th century can best be described by the speed with which cinema advanced and its visionary pioneers. Prominent among them is Edwin S. Porter, a jack-of-all-trades of turn-of-the-century America who is credited as the first filmmaker to assemble separate individual shots into a continuous sequence of parallel actions.

‘THE LIFE OF AN AMERICAN FIREFIGHTER’ (1903)

‘THE LIFE OF AN AMERICAN FIREFIGHTER’ (1903)

He began his foray into the film industry when he joined the company that marketed Thomas A. Edison’s Vitascope back in 1896. Later teaming up with Mr Edison in New York as a machinist, then as a projectionist, Mr Porter finally had the opportunity to shoot and edit his own film. In 1903, he combined stock footage of horse-drawn fire engines leaving a fire station house with staged sequences of firemen saving a woman from a burning house. Crosscuts of the rescue both inside and outside the building were compressed into a six-minute film that, for the first time, created the illusion of linear continuity.

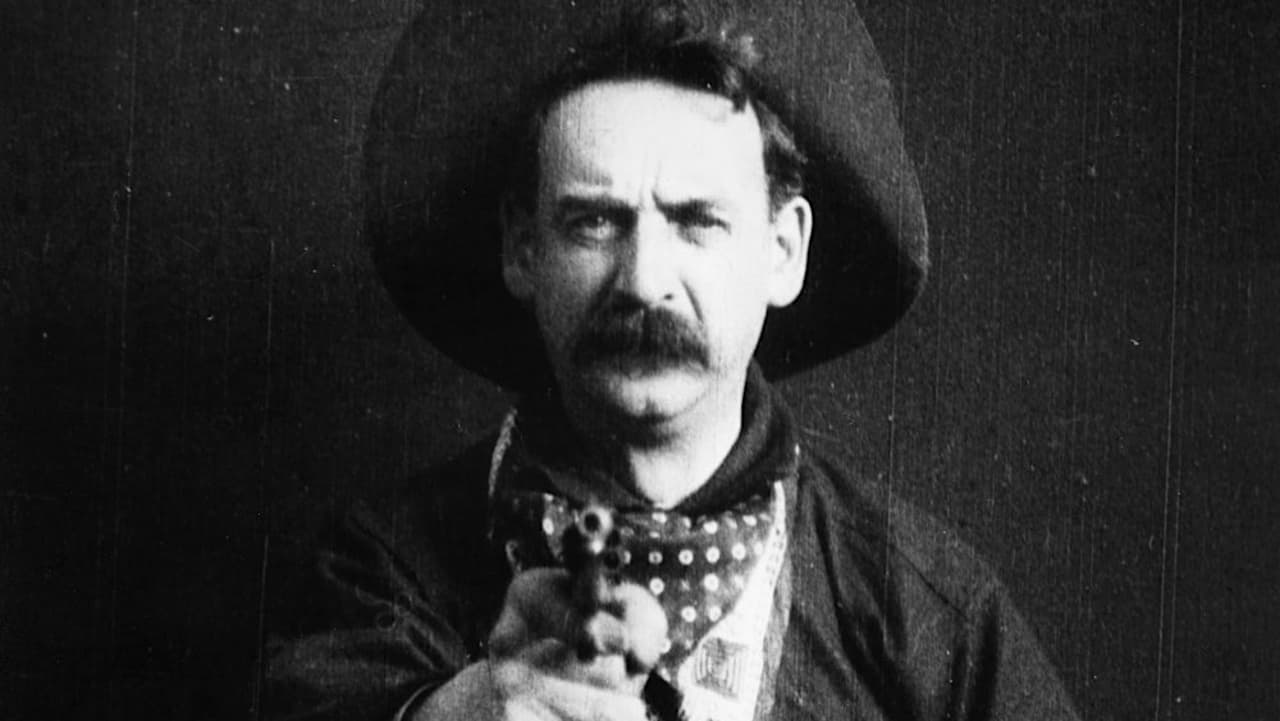

JUSTUS D. BARNES IN ‘THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY’ (1903)

JUSTUS D. BARNES IN ‘THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY’ (1903)

After ‘The Life of an American Fireman’, Mr Porter went on to create over 50 movies. Among them, his most memorable and a true masterpiece of its era remains ‘The Great Train Robbery’, also filmed in 1903. With the former, he gave us the first film where single shots were edited together to form a narrative story. With the latter, he gave us one of the best-known shots in primitive cinema—the outlaw firing at the camera. This moment of Justus D. Barnes’ outlaw character looking directly at the camera lens and emptying his revolver point blank at the audience has often been imitated since, and for good reason, too. It remains wickedly effective even for the more sophisticated modern audience.

1905: Little Hitchcock Goes to Jail

Around this time, Alfred Hitchcock recalled having ended up in prison, though he was only a child. According to Donald Spotto’s ‘The Dark Side of Genius’, which dates back from 1979, Mr Hitchcock repeated a quite memorable anecdote: ‘When I was no more than six years of age, I did something that my father considered worthy of reprimand. He sent me to the local police station with a note. The officer on duty read it and locked me in a jail cell for five minutes, saying “This is what we do to naughty boys”’. He told François Truffaut the same story 17 years earlier, and both times, he could not remember what he’d been punished for.

JUSTUS D. BARNES IN ‘THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY’ (1903)

JUSTUS D. BARNES IN ‘THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY’ (1903)

Mr Hitchcock did go on to state numerous times that his youthful incarceration might have played a part in his subsequent interest in crime and punishment. This aforementioned insistence that he didn’t know his ‘crime’ also connects to his films’ repeated emphasis on unjust penalties: in ‘The 39 Steps’ (1935), Richard Hannay is plunged into a nightmare for showing casual sexual interest; in ‘Strangers on a Train’ (1951), Guy Haines is punished for simply desiring his wife’s death; in ‘The Wrong Man’ (1956), Manny Balestrero is persecuted by a Kafkaesque justice system; and in ‘Psycho’ (1960), Marion Crane is murdered after deciding to do the right thing and return the money she stole from her employer.

Whether it is true or not, Mr Hitchcock’s prison anecdote certainly goes to show exactly how personal his work really was. In fact, most of cinema’s early productions revolve around a most intimate side of the filmmakers—their own lives and their daily observations. The very events that sparked their interest and their imagination gave birth to what is now a multi-billion-dollar industry that shows absolutely no sign of stopping. And we wouldn’t have it any other way.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.