Contemporary cinema would not exist without the artistic and technological struggles of the past. Everything that makes our audio-visual experience an extraordinary one today finds its roots in things that seemed impossible roughly a hundred years ago. The wonder of moving pictures transcended all cultural and language barriers, stirring the paying public’s imagination and desire for more.

A good story can do the same, if not more, even today. Bong Joon-Ho’s ‘Parasite’ (2019) proved just that when it won the Academy Awards for Best Motion Picture of the Year and Best International Feature Film. But before ‘Parasite’ and other Oscar darlings hit the silver screen, luminaries of the early 20th century strived to create movies for a world that had yet to fully grasp the beauty and historical importance of cinema.

To better understand the incredible evolution of this much beloved medium of artistic expression, we must peel away at the layers, decade by decade.

‘INTOLERANCE’ (1916) BY D. W. GRIFFITH, ©TRIANGLE FILM CORP

‘INTOLERANCE’ (1916) BY D. W. GRIFFITH, ©TRIANGLE FILM CORP

1906: The First Drama

26 December 1906. It was Boxing Day in the Commonwealth of Nations, and Proclamation Day in Australia. It also marked the opening of ‘The Story of the Kelly Gang’ at the Athenaeum Hall in Melbourne, proudly advertised as 4,000ft in length—roughly an hour’s runtime, which was longer than any other ‘feature’ film produced anywhere in the world.

Accompanied by an orchestra, sound effects, and a live narrator, the film was enormously popular. In the weeks that followed, ‘additional scenes’ were promoted, and multiple screenings took place all over the country. It even made it to the United Kingdom in 1907 and still billed as ‘the longest film ever made’, telling the story of the Kelly gang, notorious ‘bushrangers’ who became folk heroes for their defiance of authority and for their daring raids.

THE STORY OF THE KELLY GANG’ (1906)

THE STORY OF THE KELLY GANG’ (1906)

Ever since the capture and the hanging of the real Ned Kelly back in 1880, his gang’s deeds had become an iconic piece of Australian popular culture. Canadian actor Frank Mills played the lead role of Ned, alongside Elizabeth Tait and John Tait. Primarily responsible for this production was a family of successful theatre entrepreneurs—John, Nevin, and Charles Tait, the latter also its director. As some of the actors’ names will have already evidenced, members of their big family were also part of the cast.

‘The Story of the Kelly Gang’ was also made possible by the involvement of Millard Johnson and William Gibson, two chemists who’d taken an interest in film and, much like the Taits, had previously shown film programmes to large crowds in Melbourne. Unfortunately, and despite its roaring success, only fragments of the world’s first dramatic feature film survive today.

1908: D.W. Griffith Begins His Directorial Work at Biograph

He was merely a barely successful actor and aspiring writer when he approached the New York production house ‘The American Mutoscope & Biograph Co.’ with ideas for a few stories. His interest was noticed when he was acting on the set of one of the company’s productions, and when the house director fell ill, D.W. Griffith was offered the job on 18 June of that year.

Funny enough, Mr Griffith seemed reluctant in accepting the role at the time, worried that if he failed, it would also jeopardize his career as a writer and actor. One of Biograph’s two in-house cameramen, Billy Bitzer, gave him some coaching in film directing. From the available synopses, Mr Griffith chose ‘The Adventures of Dollie’ as his first movie, since it could be filmed on locations away from the eyes of his bosses. Despite his initial concerns, the first short film ventures were all crackling successes which led to Griffith’s becoming the studio’s principal producer-director until his departure in 1913.

D.W. GRIFFITH (2875-1948), ©GETTY IMAGES

D.W. GRIFFITH (2875-1948), ©GETTY IMAGES

This decision from Biograph ultimately positioned D.W. Griffith to play a major role in the shaping of the American cinema. Around 450 films—roughly his entire output at Biograph (1908-1913) survived, providing an inestimable marker for the transition from early cinema to the golden era of Hollywood. What made his work at Biograph seminal for the entire industry was his fearlessness in adapting existing filmic devices to the demand of storytelling.

He was at the forefront of breaking up the film narrative into a constantly growing number of shots and inserting crosscuts for suspense, or to contrast ways of life, or to get moral points across. In that sense, Mr Griffith elevated the cinematic industry to a whole new level. He combined imaginative shot selections with an eye for composition and location, along with the intensity of characterisation and performance. Griffith also played a key role in transforming the thespian art from histrionic to more realistic styles.

1910: Cinema Proves It’s More Than Seeing and Hearing

‘A Trip to Davy Jones’ Locker’ was only known by its English title when it was rediscovered in 1934 during a screening of John Grierson’s ‘The Song of Ceylon’ at the Film Society in London. All we know of it, to this day, is that it’s a French production and likely one of the first examples of ‘colour being applied direct on to the positive film’.

No one knows who directed it, or the actors’ names. This French féerie made history, however, and its nitrate copy was eventually housed at the British Film Institute. From a colourist’s point of view, it was truly an epiphany. ‘Blue, yellow, red tinting and toning were still leaping from the emulsion; splashes of other stencilled colours exploded in consecutive images until they filled the entire frame’, Paolo Cherchi Usai remembered.

©BART EVERSON/COCA COLA (NOT ACTUAL FOOTAGE FROM ‘A TRIP TO DAVY JONES’ LOCKER’)

©BART EVERSON/COCA COLA (NOT ACTUAL FOOTAGE FROM ‘A TRIP TO DAVY JONES’ LOCKER’)

It was proof that early cinema was more of a multisensory experience than we’d originally thought. There were modern copies of the film, but Mr Usai said it wasn’t the same, that the magic was gone. ‘I don’t know if the original still exists. […] it may be gone forever, in which case it will remain beautiful for as long as I can project it in my mind.’

1912: The Introduction of Panchromatic Film

Léon Gaumont asked Kodak to devise a new kind of film stock for the colour process he was developing, named Chronochrome. He needed an emulsion sensitive to the entire spectrum of visible radiations. Prior to his request, filmmakers had been using orthochromatic film, which required a modest amount of light. It was, however, fully sensitive only to certain colours (violet and blue), partially ‘blind’ to yellow and green, and unable to capture red objects at all—lipstick and roses appeared as black spots on the screen, which forced the set designers to paint their decors accordingly.

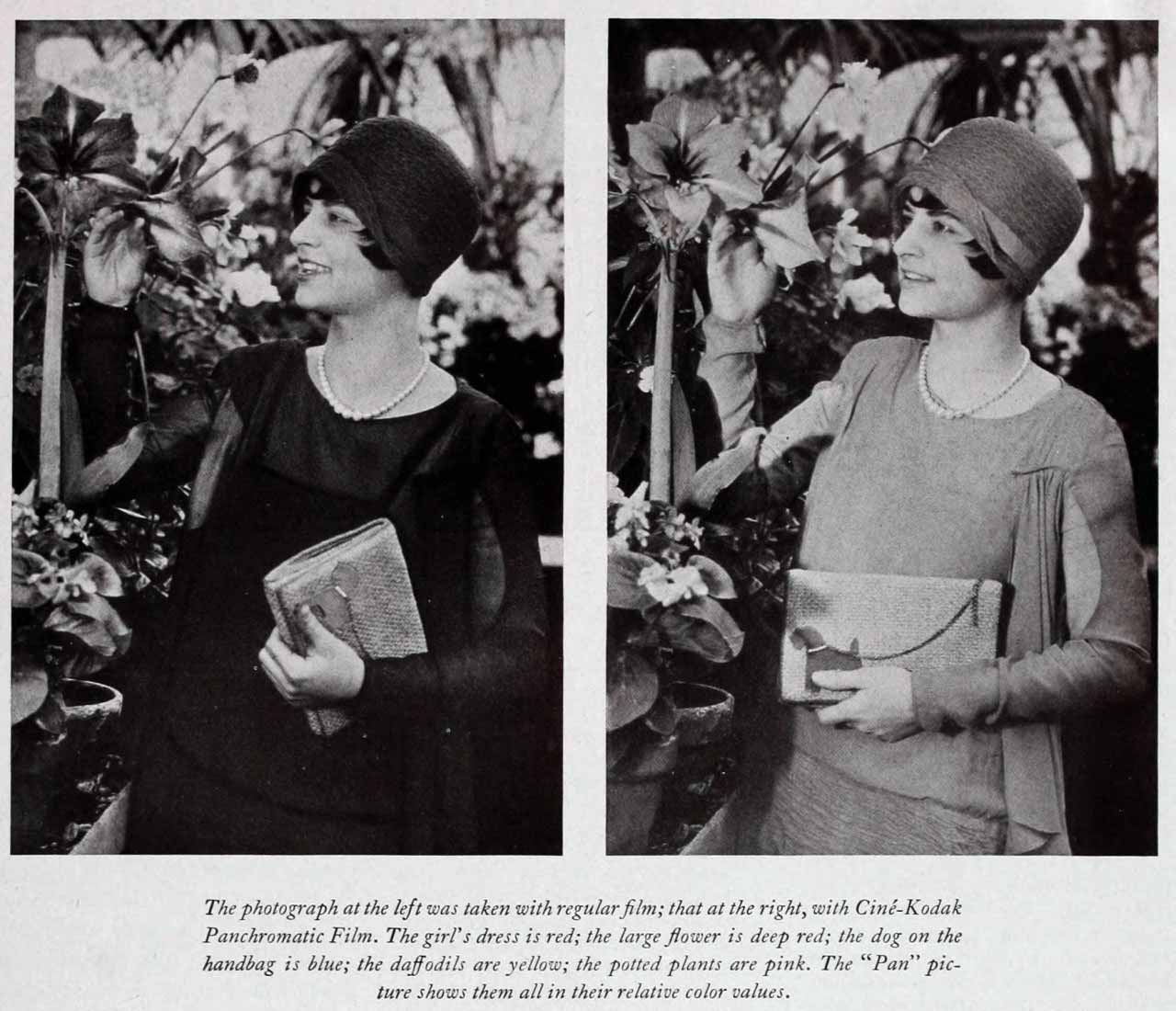

EXAMPLE OF ORTHOCHROMATIC VS. PANCHROMATIC FILM, ©TWOSTRIPTECHNICOLOR/TUMBLR

EXAMPLE OF ORTHOCHROMATIC VS. PANCHROMATIC FILM, ©TWOSTRIPTECHNICOLOR/TUMBLR

Panchromatic stock changed everything. It offered an almost infinite range of greys to the cameramen, allowing directors like Josef von Sternberg to become masters of the chiaroscuro style. It changed the way we perceived moving images, as well. Requiring much stronger set lights, panchromatic stock also meant the loss of the distinctive orthochromatic look, which can be easily observed on any original film print before the 1920s. ‘The Headless Horseman’ (1922) was the first feature-length film entirely made with the new emulsion.

1914: The Death of Intertitles

Aficionados of early cinema works will surely remember Lydia Quaranta and Umberto Mozzato in Giovani Pastrone’s ‘Cabiria’. However, not everyone knows how Pastrone lured the greedy Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio with a check of 50,000 Liras (a huge sum back then) in exchange for his agreement to appear as the ‘author’ of the film. It was a stroke of genius from a marketing point of view, and it helped push Italian cinema beyond the highbrow intellectuals’ contempt.

POSTER FOR ‘CABIRIA’ (1914), ©LATIN FILMS

POSTER FOR ‘CABIRIA’ (1914), ©LATIN FILMS

D’Annunzio’s contribution was minimal, at best, as he’d offered the first draft of the intertitles and a few suggestions regarding the characters’ names. Over the years, it became obvious that ‘Cabiria’ was Pastrone’s vision, with barely a symbolic input from D’Annunzio. What was striking about the film was its camerawork, and not its flamboyant intertitles, which were so convoluted at times that not even an Italian reader could make sense out of them.

Some were still considered as miniature poems, the last one being particularly ambiguous as it could either reflect Cabiria’s love for her hero, or the filmmaker’s love for cinema. Either way, D’Annunzio’s texts for ‘Cabiria’ were the last intertitles in a movie.

1915: A Nation Is Born on the Silver Screen

D.W. Griffith’s creation was widely recognized as the first masterpiece of American cinema. ‘The Birth of a Nation’ is, to this day, begrudgingly recognized as a key moment in the evolution of the film art. It’s impossible to separate its innovative style from the inflammatory racial issues it depicts.

It wasn’t the first time that Griffith’s thought and form blended in an unpalatable fashion. ‘The Escape’ was basically a disturbing defence of eugenics as a tool for social reform. But it was the very first shot of ‘The Birth of a Nation’ that underlined his persistence in protesting all forms of cultural censorship, convinced that he was simply telling an uncomfortable truth. This first shot makes his point crystal clear: the deportation of African slaves to America was the original sin, and the Puritan settlers of the Northern states were responsible for it.

‘BIRTH OF A NATION’ (1915), ©JERRY TAVIN/EVERETT COLLECTION

‘BIRTH OF A NATION’ (1915), ©JERRY TAVIN/EVERETT COLLECTION

In his view, the Civil War that followed between the North and the Confederate states was pure hypocrisy, dividing a nation with the pretext of defending egalitarian values which the Unionists had been the first to deny as former slave traders. The film revealed Griffith’s political thought, and it was one of the earliest ‘conversation starters’ in American cinema—as well as one of its most racist. Talk about a controversial heritage…

1916: The French Introduce the Supervillain

We’ll end this lush decade of cinematic development with Louis Feuillade’s ‘Les Vampires’, the fifth episode of a mysterious French saga that got people talking almost as much as Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation’.

The film alternated scenes of people returning to consciousness and people losing it. The thief Moréno, played by Fernand Hermann, was the archrival of the Vampires’ criminal gang. Irma, portrayed by Musidora, was his sexy accomplice.

‘MUSIDORA AS IRMA IN ‘LES VAMPIRES’ (1915)

‘MUSIDORA AS IRMA IN ‘LES VAMPIRES’ (1915)

This exciting, devious formula of the supervillain and his right hand was incredibly successful—the characters wore disguises and turned the devices of modernity against the people that they’d been invented to help. It turned criminal anarchy and terror into entertainment, which Feuillade, in turn, made into art.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.