Continuing with our series of seminal moments in the history of cinema, we leave the early days and move into a more complex and exceptionally rich decade. From 1917 until 1927, producers and directors across the globe made impressive strides in delivering movies to an increasingly more demanding audience. Stories evolved. The value of good narrative and expressive editing became a determining factor of market success.

Some of the earliest legends of the silver screen began to take centre stage, and the film world grew into the unstoppable and beautiful monster we cannot be without today. With the spike in the overall number of productions, filmmakers became bolder and tested the limits of comedy, of montage and sound, of acting styles and directorial decisions. The end results became an integral part of the world’s cinematic patrimony.

1918: The King of Comedy Is Born

Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle wasn’t just a master of silent comedy. He was also responsible for discovering new talents such as Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. ‘The Cook’, which Mr Arbuckle directed, not only demonstrates his creativity, it shows how much Mr Keaton owes to him. The two-reeler that survived is incomplete, yet the many gags squeezed within a handful of minutes of running time are enough to prove the point.

Buster Keaton is the assistant chef in a joint whose kitchen is managed by Fatty Arbuckle with a great deal of nonchalance; in-between orders, Arbuckle’s character decides to stage an improvised version of the Salome story by dressing up as the biblical character. Hilarity ensues as he puts a colander on his head, then applies frying pans and other kitchen accoutrements around his apron and over his chest to recreate Salome’s subversive dance. John the Baptist’s head is a cauliflower. This film is a key moment in cinematic history because it launched Buster Keaton’s career and it made the undeniable connection between him and Fatty Arbuckle. The latter was an established master of the comedic genre, and the former was just getting started, fated to become a legend.

‘THE COOK’ (1918), ©COMIQUE FILM COMPANY

‘THE COOK’ (1918), ©COMIQUE FILM COMPANY

1919: The Founding of United Artists

On 5 February, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith, and William S. Heart signed a contract that brought United Artists into existence. In the early days of cinema, movie moguls had been leery of even giving credit to performing artists in their productions, but public demand and commercial necessity had led to the emergence of the movie star. Four of the founders behind UA were the biggest in Hollywood at the time.

The principals, all working under various other non-exclusive contracts, were committed to making films for the company and would receive a hefty share of any profits, thus moving away from the usual meagre salaries that that actors had received until then. The problem with United Artists (as with other subsequent endeavours such as First Artists, established by Steve McQueen, Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman, and Barbra Streisand) was that the actors involved ended up using their UA deals to make non-commercial projects—Chaplin and Griffith being prime examples here.

These initiatives were derided as ‘the lunatics taking over the asylum’, eventually leading to the original artists losing control of the company before the end of the ‘20s. However, UA remained in business for another 60 years before it was bought by MGM. Learning from the past mistakes of their predecessors, Steven Spielberg, David Geffen, and Jeffrey Katzenberg founded Dreamworks SKG in 1996 and made sure to keep the word ‘artists’ out of the company’s name. Needless to say, it worked out rather nicely.

UNITED ARTISTS SIGNING

UNITED ARTISTS SIGNING

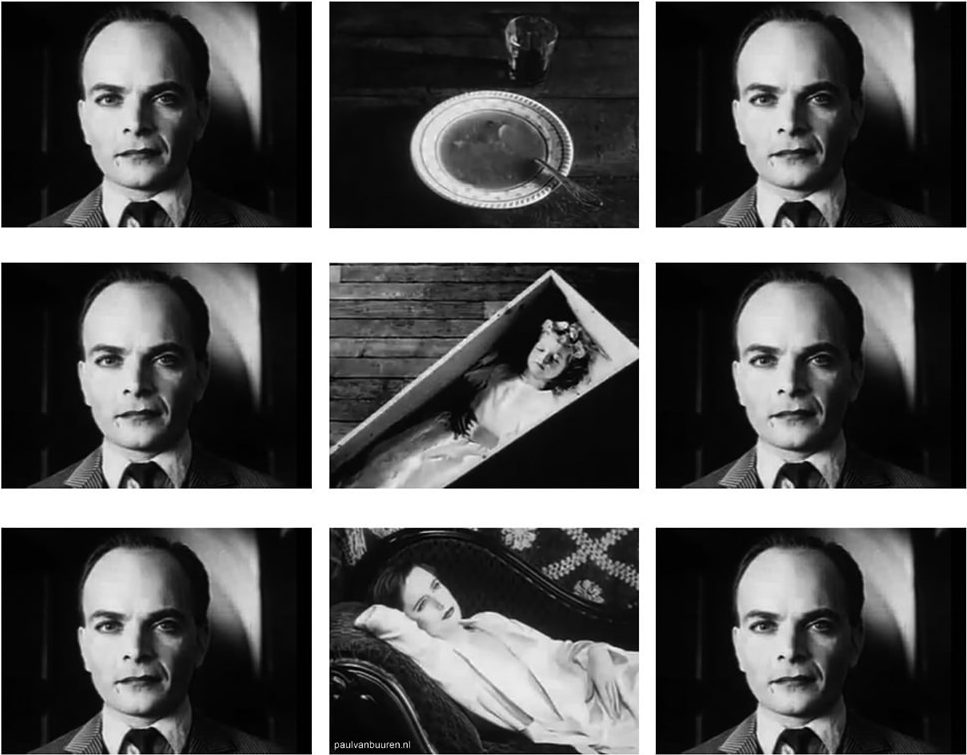

1920: The Kuleshov Effect

Around this year, Soviet director and theoretician Lev Kuleshov devised an experiment at his State Film School workshop, meant to gauge the audience’s reactions to paired images. He started by taking a close-up of pre-revolutionary matinee darling Ivan Mozhukin as he stared blankly. Mr Kuleshov then intercut this with shots of a bowl of soup, a woman in a coffin, and a child with a toy. Once it was shown to the public, the edited film caused viewers to read a remarkably appropriate emotion: hunger, sorrow, and paternal love, respectively, which were basically infused into the actor’s otherwise empty expression.

Instead of passively absorbing images, the spectators were made to feel like they had helped create meaning and thus implying a fundamental interactivity of the film medium. Today, it is considered a foundational principle of cinema, as the discovery provided theoretical foundations for Soviet-based filmmaking and proved that the content of individual shots is less significant than their sequencing.

Kuleshov, who introduced the term ‘montage’ to begin with, concluded that editing virtually changes the meaning of any shot, thus implying the primacy of director over actor and the undoubtedness of the powerful pull of intuitive truth.

EXAMPLE OF THE KULESHOV EFFECT

EXAMPLE OF THE KULESHOV EFFECT

1921: Keaton Rises and Arbuckle Falls

‘The High Sign’ was an important film of its generation. It was Buster Keaton’s first solo short after an apprenticeship in Fatty Arbuckle’s raucous comedies, and it shows his stunningly original comic invention and his mastery of the medium itself. The movie spills over with often nonsensical and borderline-surrealistic gags and situations that have already come to define Keaton’s style. But what is truly praiseworthy in ‘The High Sign’ is his sense of structure, his intricate construction of shticks and motifs that echo each other from one sequence to the next.

When rediscovered, Buster Keaton’s shorts were shown to modern audience in the ‘70s. The gag that had initially stirred barely a giggle during the film’s first release in 1921 got one of the biggest laughs of the entire movie in 1970. Undoubtedly, Buster Keaton’s comedic art wasn’t just light years away from Fatty Arbuckles’, it was way ahead of its time.

And speaking of Mr Arbuckles, his career took a devastating hit that same year. It began with Virginia Rappé’s arrival at a Labor Day party thrown by the famed comedian at the Saint Francis Hotel in San Francisco. On 9 September, the young and mostly uncredited actress died of peritonitis, caused by a ruptured bladder. Rumours soon circulated that Arbuckle was involved and had sexually assaulted her, and a flurry of grifters and lurid press coverage quickly devolved into Hollywood’s first scandal. The allegations were never corroborated, but Arbuckle became an instant pariah and was viciously blacklisted, even after three trials—the last resulting in his acquittal. During the Prohibition Era, simply holding a boozy party would’ve been enough of a shocker. Adding an accidental death in there only made it worse.

ROSCOE ‘FATTY’ ARBUCKLE, MUGSHOT

ROSCOE ‘FATTY’ ARBUCKLE, MUGSHOT

1922: The Vampire Comes to Light

F.W. Murnau made history with ‘Nosferatu’. Max Schreck played the legendary bloodsucker, and he pretty much paved the way for all the seductive monsters who later followed. Most movie vampires, from Bela Lugosi to Christopher Lee to even Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt in ‘Interview with the Vampire’ (1994) depend on charisma to capture their prey. Which is why, to this day, it’s equally unsettling to see beautiful women crumple in sleepy ecstasy as Schreck’s grotesque and shrivelled Nosferatu approaches.

The film, an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’, is pure light and darkness, and Murnau’s ability to terrorize the audience the same way the vampire charms his victims stands out. It is considered by many to be the vampire’s first appearance on the silver screen, if one is to gloss over ‘Le Manoir du Diable’ by Georges Méliès.

MAX SCHRECK AS ‘NOSFERATU’ (1922), ©JOFA-ATELIER BERLIN-JOHANNISTHAL

MAX SCHRECK AS ‘NOSFERATU’ (1922), ©JOFA-ATELIER BERLIN-JOHANNISTHAL

1924: Eisenstein Makes His Debut

‘Stachka’, better known as ‘Strike’, was the exuberant first creation of a 26-year-old Sergei Eisenstein. He justified Lenin’s visionary policy of funding cinema as an important tool for both public education and social agitation. Armed with geometric expertise from his engineering studies, Eisenstein used the story of a 1912 locomotive factory attack to teach techniques for recognizing spies and provocateurs, as well as resisting the psychological toll of a long-term strike and opposing concessions.

The film is made up of a horizontal narrative that pits heroic workers against cartoonish capitalists, and a vertical dimension that experiments with form as it depicts an event from multiple angles. The speed resembles simultaneity, and it achieves the so-called ‘cubist’ montage since Eisenstein challenges Hollywood’s seamless concealment of edits with shock juxtapositions that jolt audiences out of their habitual perception.

‘STACHKA’ (1924), ©GOSKINO/PROLETKULT

‘STACHKA’ (1924), ©GOSKINO/PROLETKULT

1925: A Year Full of Wonders

Newly formed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer invested all its cash in an adaptation of Lew Wallace’s bestseller, ‘Ben Hur’. It cost $6 million to make, and action specialist B. Reeves Eason was commissioned to re-conceive the stage adaptation’s chariot race centrepiece, which featured horses on treadmills. This was the most expensive production of the silent era, using 42 cameras to capture the sheer pulse-racing dynamism of this 12-minute ‘film within a film’. Future filmmakers took notes from such a triumphant achievement. The fast-moving spectacle and kinetic excitement of the chariot scene could later be seen in Sergei Eisenstein’s ‘Alexander Nevsky’ (1937), George Lucas’s ‘Star Wars’ (1977), Zhang Yimou’s ‘Hero’ (2002), and also William Wyler’s remake of ‘Ben-Hur’ in 1939.

‘Battleship Potemkin’ (1925) seared itself into the memory of cinema with the same force as ‘Ben Hur’. The Odessa steps sequence in Eisenstein’s magnum opus is the textbook example of his excellent theories of montage, and it has been widely imitated—not to mention endlessly discussed. The Soviet director had a perfect understanding of the film medium’s propaganda potential, thus pushing the audience into easily identifying with the people against the barbaric Cossacks during this scene. The sequence is also a flawless illustration of his dictum that ‘montage is conflict’, achieved here on both form and content.

CHARLIE CHAPLIN IN ‘GOLD RUSH’ (1925), ©CHARLES CHAPLIN PRODUCTIONS

CHARLIE CHAPLIN IN ‘GOLD RUSH’ (1925), ©CHARLES CHAPLIN PRODUCTIONS

Charlie Chaplin had an indelible effect over the world of cinema with ‘The Gold Rush’. In 1951, Theodore Huff called it ‘probably Chaplin’s most celebrated picture’, and for good reason. Though ‘The Gold Rush’ is still a classic, viewers today likely remember him better for works such as ‘City Lights’ (1931) and ‘Modern Times’ (1936), but it deserves a chance at rediscovery. The film’s dream scene basically sums up many of Chaplin’s essential qualities: his interest in dream and fantasy, his love of improvisation and ingenuity, the tremendous concentration of his face, and his artful pathos.

‘The Phantom of the Opera’ by Rupert Julian took its own seat at the table among the giants of the big screen with its unmasking scene. Even today, it is unequalled as a ‘shock’ reveal of the monster. With Lon Chaney as the Phantom, known to have designed and applied his own make-up for this film, ‘The Phantom of the Opera’ brought the monster’s shock value into the spotlight, as the viewing reportedly caused many among the original audiences to faint.

LON CHANEY AND MARY PHILBIN IN ‘THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA’ (1925), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

LON CHANEY AND MARY PHILBIN IN ‘THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA’ (1925), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

1926: The Death of Rudolph Valentino

‘The Sheik’, a hypnotizing creature of the silent film era, should have perished in a swordfight or in a firing squad execution—or anything as dramatic as his memorable characters endured on celluloid. But Rudolph Valentino succumbed to a most undignified malady at the tragic age of 31. It was a fatal peritonitis precipitated by a bleeding ulcer that did him in, and something in the public imagination went unhinged when the receptacle for so much loving flat-out disappeared. Almost 100,000 people mobbed Valentino’s wake. Their hysterical surge towards the entrance blew up into a crushing riot. The bereft crowds that mobbed New York streets in the hours after their idol’s death had no precedent for how to behave in such an instance. They didn’t know what to do with themselves. Rudolph Valentino’s death pushed celebrity worship to first reveal its dark side in the aftermath of sudden tragedy.

VILMA BANKY AND RUDOLPH VALENTINO IN ‘THE SON OF THE SHEIK’ (1926), ©FEATURE PRODUCTIONS

VILMA BANKY AND RUDOLPH VALENTINO IN ‘THE SON OF THE SHEIK’ (1926), ©FEATURE PRODUCTIONS

1925: Sound in Film

‘The Jazz Singer’ is not the first motion picture with sound. Technically speaking, Thomas Edison’s original demonstration of movies was the first to fit images with gramophone records. ‘The Jazz Singer’ isn’t even an ‘all-talking, all-singing’ picture, either, but a silent that was supposed to burst into sound whenever Al Jolson’s character got up on stage to sing.

But this historic moment of sound in film came almost by accident, as the irrepressible entertainer improvised a bit of a preamble before launching into his big number. It paved the way for the musical as a major movie genre, and it told America’s audiences that the future was already here. That this future would be continuously astonishing.

AL JOLSON IN ‘THE JAZZ SINGER’ (1927), ©WARNER BROS.

AL JOLSON IN ‘THE JAZZ SINGER’ (1927), ©WARNER BROS.

Unfortunately, and looking back on a socially and politically complicated time in the United States of America, Al Jolson and director Michael Curtiz’s accomplishment is marred by the choice of using a most hideous and incredibly racist blackface mask for the main character. The history of film never was and will never be remembered as immaculate.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.