The first half of the 20th century got off to a slow start in terms of cinema, but as the artistic medium and its technology evolved, so did storytelling for the silver screen. The golden era opened the doors for many writers, directors and actors, their names forever inscribed in the annals of movie history.

With the development of cinema came numerous milestones—from new camera movements and plot building methods to revolutionary dramatic performances and editing breakthroughs that virtually changed how we view films today. This decade further established the industry, paving the way for the billions of dollars of box office profits that followed and later turned California into one of the world’s largest economies. Of course, the changes occurred globally, with European, Russian and Asian directors making their mark. But as we take another stroll down memory lane, it’s hard not to notice that America’s contribution to the silver screen is fundamental and impossible to deny.

1928: The Genius of Comedy in the Great Depression

Charlie Chaplin’s ‘The Circus’ is one of the crown jewels of cinema. Rich in both comic invention and tender sentiment, it’s a beautifully crafted masterpiece of comedy which centres on the familiar figure of the Tramp, who inadvertently becomes the star of a circus as a clown, only to have his heart broken by Merna Kennedy’s gorgeous equestrienne. The brief final scene crystallizes all that is wonderful about Chaplin—for it is not only entirely his creation, it is also only about him.

In that moment of solitude, he is no less ‘the funny man’ the circus audience clamoured for, nor less the touching man, the resilient man, the poetic man. As Charlie Chaplin the filmmaker perceives the Tramp, he is all of the above, an eternal figure. His genius is distilled in an ending that is at once simple and sublime.

‘THE CIRCUS’ (1928), ©CHARLES CHAPLIN PRODUCTIONS

‘THE CIRCUS’ (1928), ©CHARLES CHAPLIN PRODUCTIONS

1929: From Spain and Russia with Love

Luis Buñuel’s first movie, a collaboration with Salvador Dalí titled ‘Un Chien Andalou’, is still taught in film schools today. Its ‘slice of eye’ opening scene is one of the most provocative moments in cinema. It qualifies as gore, though there’s a clear lack of realism, since the victim doesn’t move back at the sight of the blade and the special effect is obvious. The image is disturbing and voluntarily shocking, but it’s also a metaphor of the director’s desire to show us what’s really inside human beings: urges, passions, and desires. The visual assault brilliantly expresses the theoretical angle of the Surrealist revolution while simultaneously applying it.

‘UN CHIEN ANDALOU’ (1929)

‘UN CHIEN ANDALOU’ (1929)

While the Spanish were fiddling with shock value, the Russians were nurturing their documentary making skills through Dziga Vertov. In ‘Man with a Movie Camera’, the scene where the city comes to life is now remembered as a seminal moment, part of the greatest work of experimental documentary in cinema. In it, a camera seems to raise an entire city from the dead. Nearly eight decades after it was made, this film is an important chapter in academic studies, as the ‘20s Soviet Union was basically the cinematic think tank of the world. Soviet films themselves might seem ideologically shrill, but the sheer artistic joy that they exude is ever present.

Away from the European continent, however, a key event worth noting happened in the United States. On 16th May, 1929, the first awards ceremony hosted by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences concluded with the presentation of two, not one, Best Picture Oscars. Briefly making a distinction between artistic achievement and middlebrow success, the Academy gave the ‘Best Picture, Production’ statuette to William Wellman for his spectacular WWI aviation epic ‘Wings’ (1928), and the ‘Best Picture, Unique and Artistic Production’ to F.W. Murnau’s ‘Sunrise’ (1928).

‘SUNRISE’ (1927), ©FOX FILM CORPORATION

‘SUNRISE’ (1927), ©FOX FILM CORPORATION

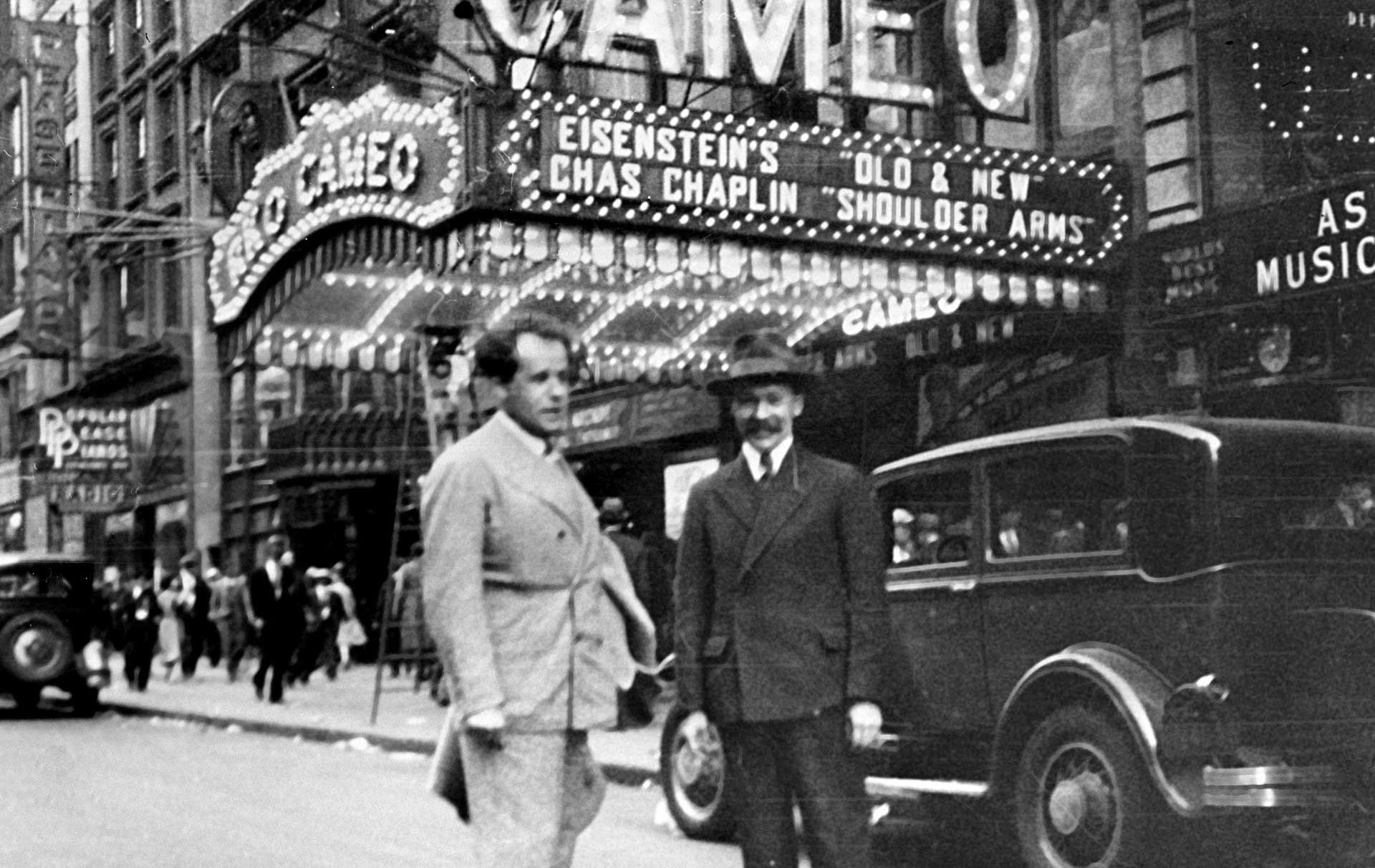

1930: Eisenstein Goes to Hollywood

After the worldwide success of ‘Battleship Potemkin’ in 1925, the Soviet government sent its star director on a tour of European capitals with the purpose of studying the new sound process. He only had $25 on him. While in Paris, Sergei Eisenstein signed a six-month contract with Paramount to develop and direct films in the movie capital. At the time, Paramount Pictures were Hollywood’s most sophisticated and continental studio, having already worked with Lubitsch, Sjöström, and Murnay—who’d already achieved artistic and financial success in the capitalist mecca.

Eisenstein had his fun while he worked in Hollywood, but he confounded expectations with his disdain for professional actors and his insistent focus on indicting capitalism, smack in the middle of ‘An American Tragedy’. A right-wing campaign then sought to deport Paramount’s ‘Jewish Bolshevik’, so the studio chose to put aside their yearning for artistic respectability. They drew a stiff line between commercial concerns and progressive art by cancelling Eisenstein’s contract. In that precise moment, profitability and formalist art forever parted ways in Hollywood.

SERGEI EISENSTEIN IN NEW YORK, 1930, ©SPUTNIK

SERGEI EISENSTEIN IN NEW YORK, 1930, ©SPUTNIK

1931: City Lights and Dracula

One of the most sublime and most definitive moments in cinema came with the last scene of ‘City Lights’. Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp is just out of prison and more down and out than ever when he meets Virginia Cherrill’s Girl—a witness to his discomfiture but also one who’s been laughing at him behind his back. When she asks: ‘You can see now?’, he says ‘Yes, I can see now.’ The film fades to black on a closeup of the Tramp looking at her, smiling but still torn between joy and a state of tension and uncertainty. It’s one of those rare scenes that doesn’t need words—so exquisite that merely remembering it is enough to bring tears through its profundity.

The vampire continued his own evolution through Tod Browning’s ‘Dracula’, starring Bela Lugosi. It is the first great talking horror film, giving us a memorable scene with Mr Lugosi’s Count as he makes a grand entrance at the top of a cobweb-draped staircase, immaculately clad in evening clothes and his black cape, saying: ‘I… am… Dracula.’ At the time, the Hungarian actor’s command of English was still shaky, so he had to learn his lines phonetically, adding to the curiousness of his cadences. Others have played the role and were required to put their own spin on the line—among them, Christopher Lee and Gary Oldman, to name but a few, yet Lugosi is still the definitive Dracula.

‘DRACULA’ (1931), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

‘DRACULA’ (1931), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

1932: Of Venus and Gangsters

Two films made history in 1932. The first, in my humble opinion, was ‘Blonde Venus’, directed by Josef von Sternberg and featuring the exquisite talents of Marlene Dietrich and Cary Grant. The ‘Hot Voodoo’ scene is especially worth remembering, as it not only marks one of the flashiest entrances of all times, it also signals the intention to subvert conventional morality—Ms Dietrich revealing herself from beneath a gorilla costume, the beauty within the beast, hirsute virility shed for teasing female eroticism.

Unfortunately, there were many racist elements in that era’s cinema; in ‘Blonde Venus’, we have the black-faced backup dancers to look past in order to see how Ms Dietrich’s character is pushed beyond the genre conventions, reinventing herself in every variety of womanhood available in Hollywood back then: devoted mother, cabaret star, drunken harlot.

‘BLONDE VENUS’ (1932), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

‘BLONDE VENUS’ (1932), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

The art of screenwriting was taken to a superior level with Ben Hecht’s penning of ‘Scarface’, directed by Howard Hawks. He was a Chicago newspaperman, a novelist and a playwright, making his entrance onto the Hollywood stage at the end of the silent era. After writing Sternberg’s ‘Underworld’, the very first gangster picture, Hecht told Howard Hughes that he could double the body count of any previous gangster film and write one twice as good. For $11,000, he finished the script in 11 days and delivered what is arguably the best of the ‘30s machinegun mafioso cycle.

‘SCARFACE’ (1932), ©THE CADDO COMPANY

‘SCARFACE’ (1932), ©THE CADDO COMPANY

1933: Nazis, Marx Brothers, King Kong

Shortly after Hitler took office, Joseph Goebbels took over the newly founded Ministry of Propaganda in March of 1933. Fritz Lang’s ‘The Testament of Dr Mabuse’, which was scheduled for its theatrical release in that same month, was banned by the Ministry’s censorship office. Not long afterwards, Goebbels allegedly summoned Lang to his office, apologized for the banning, then told him that both he and Hitler were big fans of his films, inviting him to head a new agency supervising German film production. It isn’t yet clear if Mr Lang’s account of this meeting is entirely true, but we know that a few months later, he left Germany and the Nazi regime behind.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, silent comedies continued to live on in the talkies, best exemplified by the work of the Marx Brothers. ‘Duck Soup’ gave us yet another variation of the mirror gag, which had previously been used by Charlie Chaplin in ‘The Floorwalker’ (1917) and by Max Linder in ‘Seven Years Bad Luck’ (1921)—it also inspired future productions, such as Roman Polanski’s ‘The Fearless Vampire Killers’ (1966).

‘KING KONG’ (1933), ©RKO RADIO PICTURES

‘KING KONG’ (1933), ©RKO RADIO PICTURES

Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack presented one of the great and truly iconic pieces of cinema with ‘King Kong’, the tale of the giant gorilla that took on the big city and developed a soft spot for the delectable Ann Darrow, played by Fay Wray. The greatest moment is, of course, when he stands atop the world’s tallest man-made structure with the same fierce pride and compelling dignity as at the top of his mountain on Skull Island.

1934: Frank Capra Becomes a Legend

Ten years after Harry Cohn founded Columbia Pictures, the studio had an unexpected smash with ‘It Happened One Night’. Frank Capra’s no-frills direction meshes perfectly with Robert Riskin’s rat-a-tat screenplay, giving us the now-famous scene from this original Hollywood romantic comedy: Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert must share a rural motel room; he uses a blanket he dubs ‘the walls of Jericho’ to block their views from each other, and a delightful, ageless dialogue ensues. ‘It Happened One Night’ was one of the first films to win all top-five Oscars—production, director, actor, actress, and screenplay.

‘IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT’ (1934), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

‘IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT’ (1934), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

1935: Technicolor Vanity Fair

Rouben Mamoulian’s ‘Becky Sharp’ is an impudent stripping down of Thackeray’s classic panorama of social climbing. It caused quite a few monocles to drop at the time. But despite the film’s witty nuances and Miriam Hopkins’ stellar performance, its core purpose was to display the new technology of three-strip Technicolor, which was finally perfected after twenty years of experimentation. The old processes only registered variations of red and green, while the new one used with ‘Becky Sharp’ offers brilliant, distinct shades of buttercup yellow, burnt orange, and Wedgwood blue, along with a more natural skin tone—a technological landmark in film history.

‘BECKY SHARP’ (1935) RESTORED THREE-STRIP TECHNICOLOR SHOT, ©PIONEER PICTURES CORPORATION/UCLA FILM & TELEVISION ARCHIVE

‘BECKY SHARP’ (1935) RESTORED THREE-STRIP TECHNICOLOR SHOT, ©PIONEER PICTURES CORPORATION/UCLA FILM & TELEVISION ARCHIVE

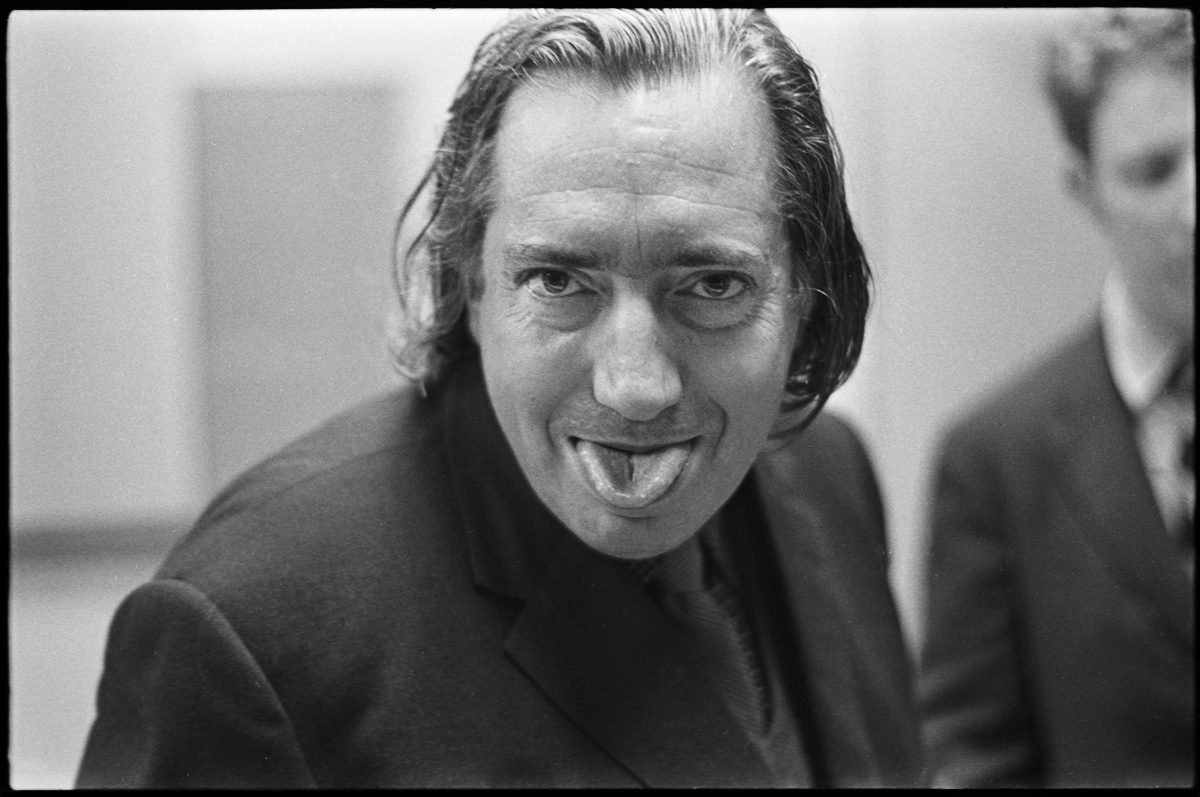

1936: The Foundation of the Cinémathèque Française

Most of us likely remember Ernest Lindgren from the United Kingdom, Jacques Ledoux from Belgium, Henri Langlois from France, and Iris Barry in the United States as founding fathers and mother, respectively, of film archives. They all shaped the art and science of collecting, preserving, and making available the moving image heritage for posterity at a time when cinema was merely seen as a minor form of art. But it was thanks to Henri Langlois’ efforts of establishing the Cinémathèque Française that turned the endeavour into a cultural phenomenon.

It is only his name that is associated today with the venerable institution, and that is mostly because of Mr Langlois’ knack of turning his passion into a ‘cause célèbre’. His agitprop genius helped propel the Nouvelle Vague movement, and his way of amassing and concealing film prints is pretty much the stuff legends are made of.

HENRI LANGLOIS, ©STEVE MUREZ

HENRI LANGLOIS, ©STEVE MUREZ

1938: Angels with Dirty Faces

To this day, Rocky’s death scene is still shocking—James Cagney’s screams sound so real. Nevertheless, what an incredible Hollywood-schmaltz moment!

Convicted for the murder of a double-crossing, no good rat played by Humphrey Bogart, Cagney’s Rocky Sullivan is visited by Father Jerry, his boyhood friend, the night before he’s due to die on the electric chair. Rocky promises to die the way he lived, spitting in the eye of authority and refusing to give anyone the satisfaction of seeing him break.

‘ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES’ (1938), ©WARNER BROS.

‘ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES’ (1938), ©WARNER BROS.

His demise is perhaps one of the most chilling snippets ever projected onto the big screen. Realizing that the youngsters who adore him might end up just like him, Rocky puts on a cowardly act and starts screaming as he’s dragged off the next morning to his execution, as a last attempt at pushing others away from his path. It turns him into a genuine martyr, as he proves he is man enough to recognize his fragility and to do one last good thing in this world.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.