Going into the modern chapters of film history, we will observe a rapid development of special effects and editing technologies, along with a continued evolution of the blockbuster and the merchandising empires that come with it. At this point, stories and characters continue to grow, and racial and political issues begin to take centre stage, giving us a plethora of seminal moments to pick from for a more in-depth study.

To sum things up, however, the Eighties were not just about bad hair and trashy cult flicks, and the early Nineties represent a threshold into adulthood for modern cinema, with an increasing diversity in storytelling. From 1983 until 1993, the film industry continues with its steady course upwards, further claiming its strength as an essential source of entertainment and as a soft power.

1983: The Year of Satire and Cocaine

One of the most memorable films to come out of the Eighties was Martin Scorsese’s ‘The King of Comedy’ (1983), a dark satire that culminates with a truly epic moment between Martin Scorsese’s fame-hungry Rupert Pupkin and Jerry Lewis’s comic legend Jerry Langford, as the ardent desire for celebrity becomes a blatant invasion of privacy. This scene features Rupert uninvited in Jerry’s home and accompanied by Diahnne Abbott’s Rita, with an awkward conversation that escalates into something… extraordinary.

The modern sculptures it takes place around sort of lend it an air of Greek drama and grandiosity, with Jerry in his shorts and sneakers looking stoic and regal going against Rupert, with his little moustache and two-toned shoes—a jester prancing and foretelling a dawn of shamelessness as a personality cult soon to engulf the world. ‘I’m gonna be 50 times more famous than you!’ Rupert ends up yelling at Jerry, ultimately confusing talent with fame.

‘THE KING OF COMEDY’ (1983), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

‘THE KING OF COMEDY’ (1983), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

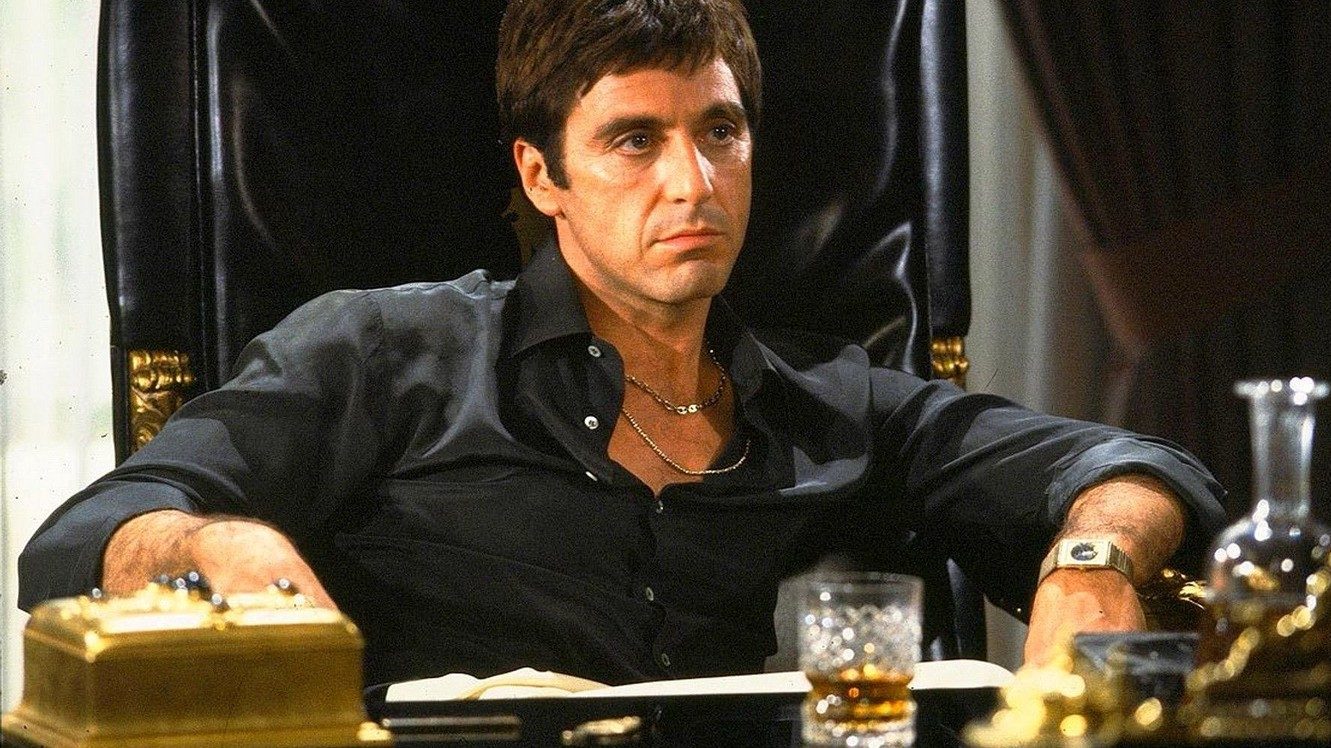

With ‘Scarface’ (1983), Brian De Palma offers a melodramatic, if not even opera-like extreme approach to the classic theme of the gangster. It centres on Tony Montana’s (Al Pacino) obsession with territorial control, mercilessly followed by the loss of this power. He’s a Cuban refugee who is intent on living his version of the American Dream by gaining absolute control over everyone and everything.

However, at the end of this extravagant rise and fall, shortly after snorting a literal mountain of cocaine, Tony Montana gives us an outrageously hyperbolic finale that ends in blood and bullets. It was considered vulgar and politically insensitive shortly after its release, yet it has withstood the test of time as a masterpiece of modern cinema that gives us the subversive thrill of watching a social microcosm explode.

‘SCARFACE’ (1983), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

‘SCARFACE’ (1983), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

1985: A Dystopian Dream

Terry Gilliam’s ‘Brazil’ (1985) gave a whole new meaning to the term ‘dark comedy’. A burning science-fiction fantasy about a future gone many kinds of wrong, the film got off on a tremorous start when Universal Pictures, its American distributor, declared it a failure and refused to release it. Mr Gilliam, ever the stubborn and enterprising spirit, arranged press screenings anyway. Once the Los Angeles film critics declared it the best movie of the year, Universal relented.

In hindsight, it’s not difficult to understand why the studio had trouble seeing its potential. ‘Brazil’ steers clear of the regular commercial categories. The hero of this story, Sam, exquisitely portrayed by Jonathan Pryce, is a bureaucrat in a future society that might be considered totalitarian, if not for its endless stream of blunders and almost-cartoonish errors. He’s branded a terrorist, eventually, and goes through a series of harrowing experiences before he is saved—only to find out that his breathless escape was nothing more than a hallucination. Sam has surrendered unto the worst torture of all—the foolishness of hope.

‘BRAZIL’ (1985), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

‘BRAZIL’ (1985), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

1986: The Cinema of Strange

‘Blue Velvet’ (1986) is one of David Lynch’s best films, its ‘In Dreams’ scene best representing the director’s mastery of bizarre juxtaposition. Dean Stockwell’s Ben, hailed by Dennis Hopper’s Frank as ‘one suave f***er’, takes down a mobile mechanic’s light and uses it as a lounge singer’s microphone, lip-syncing to Roy Orbison’s classic ‘In Dreams’. It’s a signature of Lynch’s—taking easy listening melodies and presenting them in a manner that unmasks the fetishism, the obsession, and the dreamlike delirium that lingers behind their charming golden-oldie familiarity.

Ben is effeminate but lethal, his face covered in white kabuki makeup as he assaults Orbison’s song, projecting the entirety of his putrid soul into its soft, elusive, and twisted lyrics. The song is later replayed when Kyle MacLachlan’s Jeffrey is savagely beaten by Frank’s goons.

‘BLUE VELVET’ (1986), ©DE LAURENTIIS ENTERTAINMENT GROUP (DEG)

‘BLUE VELVET’ (1986), ©DE LAURENTIIS ENTERTAINMENT GROUP (DEG)

It was also the year of John Woo. ‘A Better Tomorrow’ (1986) is the legendary director’s breakthrough film, in which he coins an elegant cinematic language that redesigns the Hong Kong gangster genre, propelling Chow Yun-Fat to international fame. In its most famous scene, Chow’s dashing gangster Mark lights his cigarette with a fake hundred-dollar bill before he enters a restaurant and delivers an almost musical performance in fighting the traitorous gangsters, his figure as feathery as Fred Astaire’s.

1987: Of Chinese Superstars and American Soldiers

Zhang Yimou’s first film, ‘Red Sorghum’ (1987) recorded an incredible international success and created one of the most well-regarded professional couplings in cinema altogether—for there are few as wonderful as Zhang Yimou and the arresting Gong Li. Of course, there was also a personal layer to this pair, as the two developed a long-lasting relationship despite Mr Zhang’s marriage, his wife refusing to grant him a divorce.

It was in ‘Red Sorghum’ that the world became familiar with 22-year-old Gong Li as the bride with a lustful smile in a crimson palanquin, forever transforming Chinese cinema. She was reunited with Zhang for two other great films, ‘Ju Dou’ (1990) and ‘Raise the Red Lantern’ (1991), contributing to the director’s global fame and helping to usher in a new ‘star system à la chinoise’ that was easily exported to the West.

‘RED SORGHUM’ (1987), ©XI’AN FILM STUDIO

‘RED SORGHUM’ (1987), ©XI’AN FILM STUDIO

An iconic film of the Eighties—one that haunts its first viewers to this day, is Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Full Metal Jacket’ (1987). It’s a powerful work of silver screen art, and this power is incredibly condensed into the closeup of the dying Vietcong woman. Kubrick has no military or wartime experience whatsoever, yet he delivers a gut-wrenching scene with the wounded sniper who begs for Matthew Modine’s Joker to finish her off. The hatred in her eyes is absolute, making this particular scene impossible to forget, especially once we see ‘Gomer Pile’ grinning insanely just before he shoots Sergeant Hartman.

‘FULL METAL JACKET’ (1987), ©STANLEY KUBRICK PRODUCTIONS

‘FULL METAL JACKET’ (1987), ©STANLEY KUBRICK PRODUCTIONS

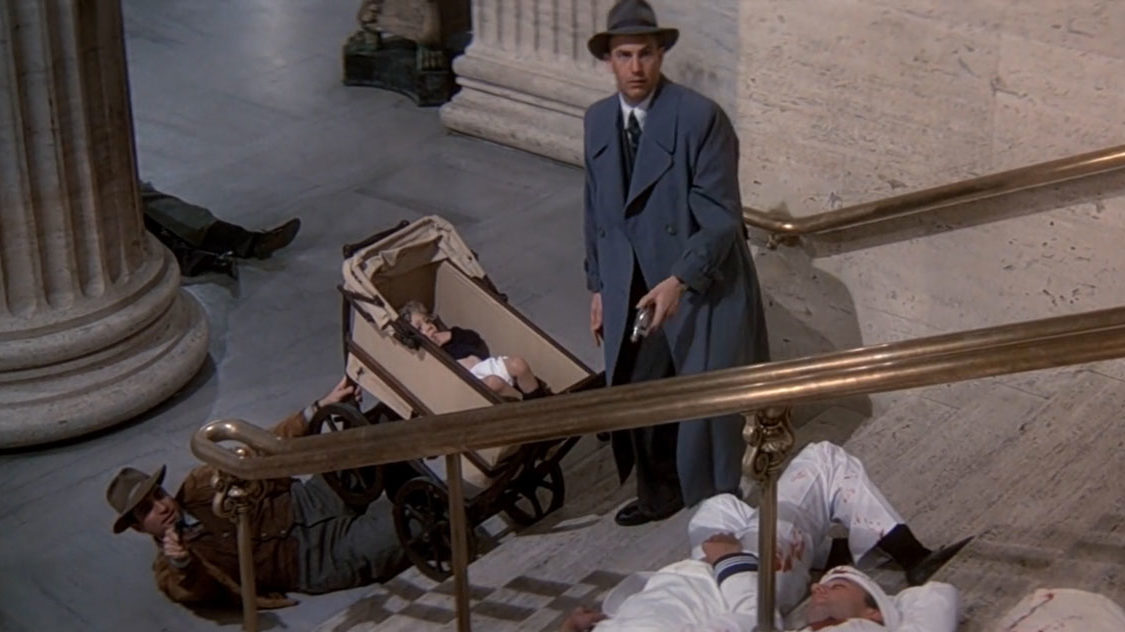

In Brian De Palma’s ‘The Untouchables’ (1987), the showdown at the train station is a veritable work of art. It’s also a splendidly crafted update of a legendary silent-film sequence that ultimately demonstrates the perennial life force of pure visual storytelling. Ennio Morricone’s score gives it a final dash of authenticity. Kevin Costner’s Eliot Ness and his partner, played by Andy Garcia, are determined to capture Al Capone’s bookkeeper. In David Mamet’s original screenplay, this was supposed to happen as the accountant’s train was pulling out of Chicago’s Union Station. Paramount stuttered at the cost of production, asking De Palma to shoot the whole scene inside.

Regarding himself as a visual stylist who cares not for where his plots come from, De Palma thus shows us why he’s one of cinema’s greatest borrowers by taking a cue from Eisenstein’s ‘Battleship Potemkin’ (1925) and refurbishing the ‘Odessa Steps’ scene for Eliot Ness through montage and alternating shots that inflate tension.

‘THE UNTOUCHABLES’ (1987), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

‘THE UNTOUCHABLES’ (1987), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

1988: The Rise of Anime and the Impact of Film on Real Life

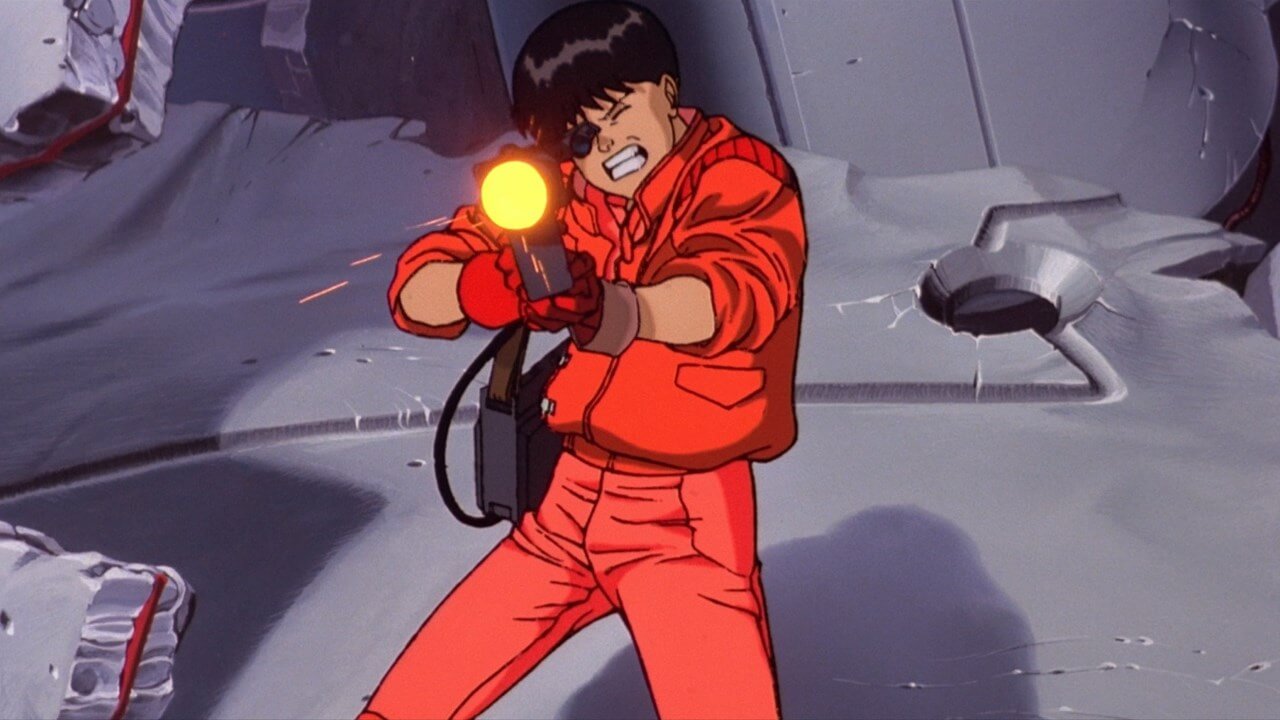

Before Katsuhiro Otomo’s ‘Akira’ (1988), most Westerners considered Japanese animation to be cartoons like ‘Speed Racer’, kids’ stuff with technical shortcuts and annoying overdubs. But the Japanese director gifted his dystopian epic animation feature with a convoluted plot, plenty of graphic violence and hallucinatory visuals, a dollop of black humour, an incredible attention to detail and a minutely synched dialogue sprinkled with meditations on evolution, enlightenment, and mass destruction. In ‘Akira’, Tokyo exploded on 16th June 1988, and the world was never the same again. ‘Akira’ was theatrically released on 16th June 1988, and the real world was never the same again, either, as the Japanese animated feature paved the way for illustrious works such as Studio Ghibli’s ‘Spirited Away’ (2001) and ‘Ghost in the Shell’ (1995).

‘AKIRA’ (1988), ©AKIRA STUDIO/TMS ENTERTAINMENT

‘AKIRA’ (1988), ©AKIRA STUDIO/TMS ENTERTAINMENT

Meanwhile, in the United States, Errol Morris’s ‘The Thin Blue Line’ (1988), presented as a non-fiction film noir, was universally applauded as a masterpiece of unconventional documentary that ultimately got an innocent man out of prison. The filmmaker and private detective began his journey with ‘The Thin Blue Line’ by making inquiries about James Grigson, a forensic psychiatrist known as a star witness in major capital murder cases. After interviewing him and some of the felons he’d put on death row, Morris became fixated on Randall Adams, in particular, who resolutely swore he was innocent.

By combining talking-head interviews, re-enactments, photographic evidence, and Philip Glass’s hypnotic score, Morris created a visual poem of slowly surfacing evil that climaxes with David Harris, the teenager whose confession put Adams in prison in the first place, as he finally reveals the truth. Because of the evidence presented in this film, Randall Adams was released from jail in 1989.

RANDALL ADAMS IN ‘THE THIN BLUE LINE’ (1988), ©AMERICAN PLAYHOUSE

RANDALL ADAMS IN ‘THE THIN BLUE LINE’ (1988), ©AMERICAN PLAYHOUSE

1989: Of Avid and Blockbusters

The last year of the Eighties was a fruitful one. In April, Avid introduced the film industry to digital nonlinear editing with its Avid/1 Media Composer system, which revolutionized the postproduction process by ‘providing editors with a faster, more intuitive, and more creative way to work than was possible with traditional analogue linear methods’. It didn’t just change the filmmakers’ view on the editing process, it also changed the way films looked. Digital editing confirms the status of image and sound as data, freeing them from their material support, as they’re no longer dependent on strips of film and tape. This was the true birth of digital cinema.

Though cynically conceived, Tim Burton’s ‘Batman’ (1989) was an absolute smash, generating five sequels, a new animated series, an animated movie, and billions of dollars’ worth of branded merchandise. It made George Lucas’s success with ‘Star Wars’ seem almost quaint by comparison. In the end, ‘Batman’ perfected the blockbuster as a product, a concept that was still new to the suits in Hollywood at the time. What Lucas’s film was to the Seventies, Burton’s was to the Eighties—an iconic distillation of its era, further named ‘the film of the decade’ by Peter Travers of Rolling Stone magazine.

‘BATMAN’ (1989), ©WARNER BROS.

‘BATMAN’ (1989), ©WARNER BROS.

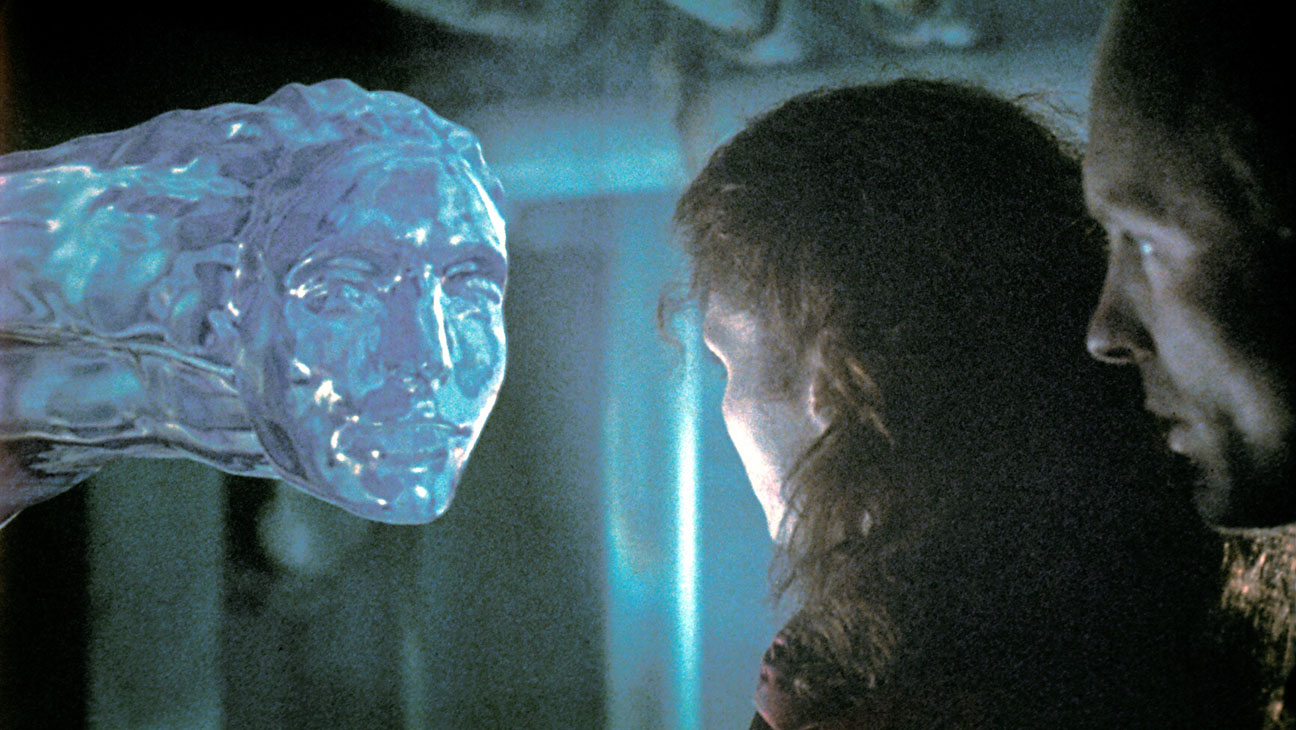

The one moment that everyone remembers from James Cameron’s ‘The Abyss’ (1989) is the water tentacle. This set piece, organic rather than mechanic, was as revolutionary as the first sound in the moving pictures. Within months from its premiere, other ambitious movies moved to development, including Cameron’s ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’ (1991) and Spielberg’s ‘Jurassic Park’ (1993), and they were built entirely around CGI creations. Back then, when the scene was shot, no one knew if the effect would work, so these CGI-dependent sequences were written in a way that made it easy to cut them out if the computer programmers failed to deliver the proper effect. The tentacle of ‘The Abyss’ basically kickstarted computer-generated graphics in cinema.

‘THE ABYSS’ (1989), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

‘THE ABYSS’ (1989), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

Spike Lee made history with ‘Do the Right Thing’ (1989), a defining moment for New Black Cinema. The director wrote, directed, and led the cast onscreen, conforming to the era’s do-it-yourself model of African American cinema—previously adopted by the likes of Oscar Micheaux in the Twenties and Melvin Van Peebles in the Seventies. But no other Black American filmmaker had ever won such a public platform as Spike Lee even before he released ‘Do the Right Thing’, a simmering drama about racial tensions in America, as experienced right then in those days in Brooklyn. The film further propelled him as a master of the silver screen. It also earned a couple of Oscar nods for Best Screenplay and Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Danny Aiello).

‘DO THE RIGHT THING’ (1989), ©40 ACRES & A MULE FILMWORKS

‘DO THE RIGHT THING’ (1989), ©40 ACRES & A MULE FILMWORKS

1991: Driving Off a Cliff

The unexpected conclusion of Ridley Scott’s road drama ‘Thelma and Louise’ (1991) sparked a wave of consternation and controversy from viewers and critics alike. It was a conversation piece in the early Nineties, especially since its lead characters were women—there already were ample discussions about the representation of female characters in pop culture at the time, along with Hollywood’s blatant appropriation of feminist motifs.

In ‘Thelma and Louise’, two working class women from Arkansas hit the road after they confront and kill a brutal would-be rapist. Their decision to drive off the cliff at the end of their fiery journey annoyed academic and feminist commentators, too, though the film did earn an equal amount of praise for its screenplay and manner of dealing with hot button topics such as rape and spousal abuse from a woman’s perspective.

‘THELMA AND LOUISE’ (1991), ©PATHÉ ENTERTAINMENT

‘THELMA AND LOUISE’ (1991), ©PATHÉ ENTERTAINMENT

‘The Silence of the Lambs’ (1991) by Jonathan Demme made for an equally compelling start to the decade. Hailing from Roger Corman’s B-movie generation, Demme was a natural with the chilling and sensationalist source material of Thomas Harris’s second Lecter novel after ‘Red Dragon’. Few, however, expected a film of such deliberate rigour, so neatly matched to Ted Tally’s screenplay, almost word by word. The first meeting between Jodie Foster’s Clarice Starling and Anthony Hopkins’s Hannibal Lecter is proof, as the young FBI recruit is ‘wide-eyed with terror yet stubbornly determined not to wilt in the heat of pure evil’, as David Stratton once wrote. This sinister sequence is complex and beautifully crafted, coming across as an example of Demme’s thinking-man’s-thriller style.

‘THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS’ (1991), ©STRONG HEART/DEMME PRODUCTION

‘THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS’ (1991), ©STRONG HEART/DEMME PRODUCTION

1993: Postmodernist Cinema à la Kusturica

‘Arizona Dream’ (1993) wasn’t Emir Kusturica’s greatest film—my eternal favourite will forever be ‘Black Cat, White Cat’ (1998). But it is a superb example of cinematic postmodernism, with wonderful performances from Johnny Depp, Vincent Gallo, and Faye Dunaway. The sequence where Paul (Vincent Gallo) ‘performs’ Cary Grant’s crop-duster attack from Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘North by Northwest’ (1959) is magnificent. Shot by shot, albeit with only four stalks of corn as props behind him, Paul does an exact reconstruction, leaving us to imagine each buzz of aircraft flying overhead.

‘ARIZONA DREAM’ (1993), ©CANAL+

‘ARIZONA DREAM’ (1993), ©CANAL+

This moment requires us to see two movies at once and overlapped, offering laughter as we notice the titanic differences between Paul’s performance against Cary Grant’s. That was the point of it, in the final analysis, to take advantage of this little pocket in time to feast on a slice of absurdity.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.