For the sake of brevity, a tight selection had to be made for this second part of our foray into Japan’s cinematic history. Truth be told, the wholly defining moments of the Japanese silver screen mostly belong between the late Fifties and the late Eighties, as the rest of Asia rises and takes centre stage.

In the sunset of Akira Kurosawa’s career, Hong Kong and South Korea were budding stars—not to mention India, Taiwan, and even mainland China. Rest assured, however, that what we’re about to delve into is a melange of Japanese cinema’s most precious and pivotal moments, the twists and turns that redefined an entire industry and perfected the craft whilst dabbling in concepts of surrealism and minimalism.

‘Sansho the Bailiff’, 1954

A mother’s sorrowful call echoes across time and space in Kenji Mizoguchi’s mid-century masterpiece, a scene that is ultimately enhanced by the director’s use of a near-infinite expanse. ‘Sansho the Bailiff’ is a burning drama centred on a family torn apart by medieval brutality. Two children were kidnapped and sold into slavery on the Japanese mainland. They’re now grown, and we only learn that their mother is still alive when we see her atop a hill, gazing out into the distance and toward the mainland, as she calls out their names. ‘Anzu… Zushio…’

The men have taken other names, in the meantime, which further adds to this moment’s poignancy. Mizoguchi’s decision to accentuate the sound of the children’s names—the extension of the vowels, in particular, seems to evoke the vast space and years that separate these three characters. The affecting transience suggested here of individual lives in the face of history ends up resonating with what is arguably one of the most emotionally wrenching sound snippets in Asian cinema.

‘SANSHO THE BAILIFF’ (1954), ©DAIEI STUDIOS

‘SANSHO THE BAILIFF’ (1954), ©DAIEI STUDIOS

‘I Live in Fear (aka Record of a Living Being)’, 1955

Dr Harada must judge the mental competence of Nakajima, a foundry owner who is desperate to leave Japan before what he considers an inevitable nuclear holocaust. It’s a moral dilemma for the judge, really, as he represents the typical bourgeoisie of that era. He fails to understand that this particular problem cannot be resolved in clinical terms of ‘sanity’ or ‘insanity’. On the opposite side of the ideological spectrum in Akira Kurosawa’s ethically and morally loaded drama is Nakajima, who is best described as ‘designed to simply take everything too far’.

In the final shot, Kurosawa demonstrates his ability to condense the overall theme of the film into standalone images of extraordinary resonance. On the left of the screen, we’ve got Harada walking down a staircase. He’s leaving the asylum where Nakajima has been committed. On the right, Nakajima’s mistress walks along a corridor, though she is framed as if moving toward the top of the screen. An unchangeable, descending old man is juxtaposed yet separated from a woman ascending—the latter gives Nakajima money and makes it clear that she has no interest in having him acknowledge that he’s the father of her child. This entire moment is an overlap of pieces that boil down to one hard truth. Asako, the mistress, is the truly ‘Living Being’, not Nakajima, for she is motivated by something other than self-interest.

‘I LIVE IN FEAR’ (1955), ©TOHO COMPANY

‘I LIVE IN FEAR’ (1955), ©TOHO COMPANY

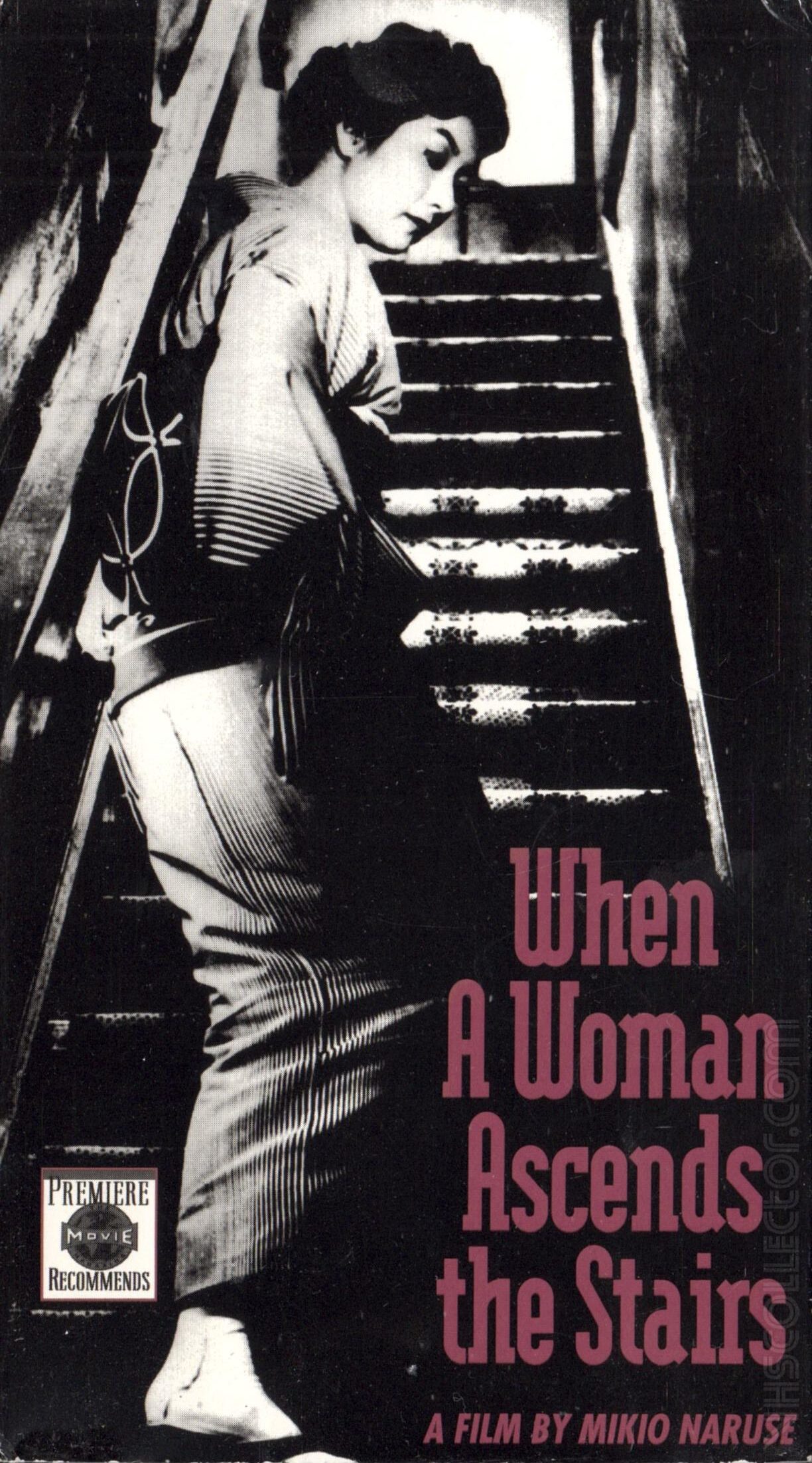

‘When a Woman Ascends the Stairs’, 1960

Mikio Naruse’s film is artistically defined by the narrow confines of space in which its leading lady is forced to dwell—and by confines, I mean not only physical tight spots but also social and emotional. As Keiko feels the world turn in a moment of incredible expressive power in what I’m comfortable defining as the climax of ‘When a Woman Ascends the Stairs’, the character, the plot, the setting, and the camera movement merge and become one.

The staircase itself is as narrow as a coffin and dimly lit. It’s an integral part of her tiny world at Ginza, where Keiko begins to realize that she is no longer young yet still a prisoner, still stuck in cramped spaces, unable to… ascend. She’s got debts to pay, a family to support. Her only choice is to keep smiling while she tries to find her way out. When she is finally out in the open, climbing a hill in the Tokyo suburbs, we’re briefly fooled into thinking that this is it. Keiko’s true freedom is right at the top of the mound. Alas, here, she learns that her supposed escape route has been foiled. The camera doesn’t stop, moving with Keiko and studying the panoramic views that have been missing from the movie until now. For the first time, the CinemaScope frame is bursting with a landscape, yet Keiko looks out at the endless possibilities—of which none are nor ever will be hers.

‘WHEN A WOMAN ASCENDS THE STAIRS’ (1960), ©TOHO COMPANY

‘WHEN A WOMAN ASCENDS THE STAIRS’ (1960), ©TOHO COMPANY

‘The Mad Fox’, 1962

Because he’d taken to using an extremely diverse range of styles, Tomu Uchida had yet to make his mark on the West. His films were remarkable pieces of cinema, of course, but Americans and Europeans had yet to adjust to his multitude of narrative and audio-visual elements. Nevertheless, ‘The Mad Fox’ propelled him to international fame because of its surprisingly singular style. It’s a widescreen period piece about love and betrayal, heightening artificiality with stunning results.

We’re mesmerized by the Van Gogh yellow fields and papier-mâché décor, charmed by the fairy tale vixens and even animated flames. The hero of the story surrenders unto madness, delving into a finale that is downright theatrical. Realizing that his dreams of love and happiness were nothing more than illusions, his whole world falls apart—quite literally, as the stage-scenery-house in which he lived them collapses in on itself. In this singular fusion of film and theatre, Mr Uchida offers an eye-popping, hysterically colourful fantasy that delves into the protagonist’s mind before he tops it off with a literal and astonishing breakdown.

‘THE MAD FOX’ (1962), ©TOEI KYOTO

‘THE MAD FOX’ (1962), ©TOEI KYOTO

‘Tokyo Drifter’, 1966

Seijun Suzuki was better known for his struggle between genre and art. In contrast, this film symbolizes his career shift and foreshadows the following year’s ‘Branded to Kill’, which was deemed ‘incomprehensible’ by Nikkatsu boss Kyusaku Hori and led to the director’s ousting. However, the fan protests resulting from his dismissal became representative of a period’s end in Japanese cinema—the death of the studio era, to be specific. ‘Tokyo Drifter’ was pretty much the catalyst, and one scene from it stands as the most memorable.

In this gangster masterpiece, Tetsu walks down an exceptionally narrow corridor before the final battle. Geometric, emblematic spaces define the film, courtesy of art director Takeo Kimura, in direct opposition to Tetsu’s own nature. He only has one chance to get this right. He counts out the steps he must run along the rail line before firing the fatal shot. In the climax, Tetsu desperately needs room to move, and so emerging from that corridor to finish the job is the right choice—much like Seijun’s own career choices were risky but ultimately led to greater successes.

‘TOKYO DRIFTER’ (1966), ©NIKKATSU

‘TOKYO DRIFTER’ (1966), ©NIKKATSU

‘A Man Vanishes’, 1967

The moment we realize that we’re no longer watching a documentary is a key point in the evolution of Japanese cinema, made possible by Shohei Imamura’s unyielding filmmaking vision. Orson Welles pulled off something relatively similar later in 1973 with ‘F Is for Fake’, where he promised to tell only the truth for precisely an hour, then swiftly slipping back into magic and lies. Yet Imamura’s shape-shifting of reality is even more enticing, since the film begins as a documentary. A promise of factual truths has already been made, and it doesn’t have an expiration date.

But as Yoshie the faithful wife persists in a rigorous search of her missing husband, taking us to a tea house toward the end of the movie, we learn that the man may have last been seen with another woman. A moment later, Imamura can be seen in the shot. Someone tells him something. ‘OK, strike the set’, he replies, and we cut directly to a scene where stage hands knock down hardboard walls. We’re on a set! Somewhere along the investigative thread of ‘A Man Vanishes’, Yoshie lost interest in finding her husband and became enamoured with Imamura.

‘A MAN VANISHES’ (1967), ©IMAMURA PRODUCTIONS

‘A MAN VANISHES’ (1967), ©IMAMURA PRODUCTIONS

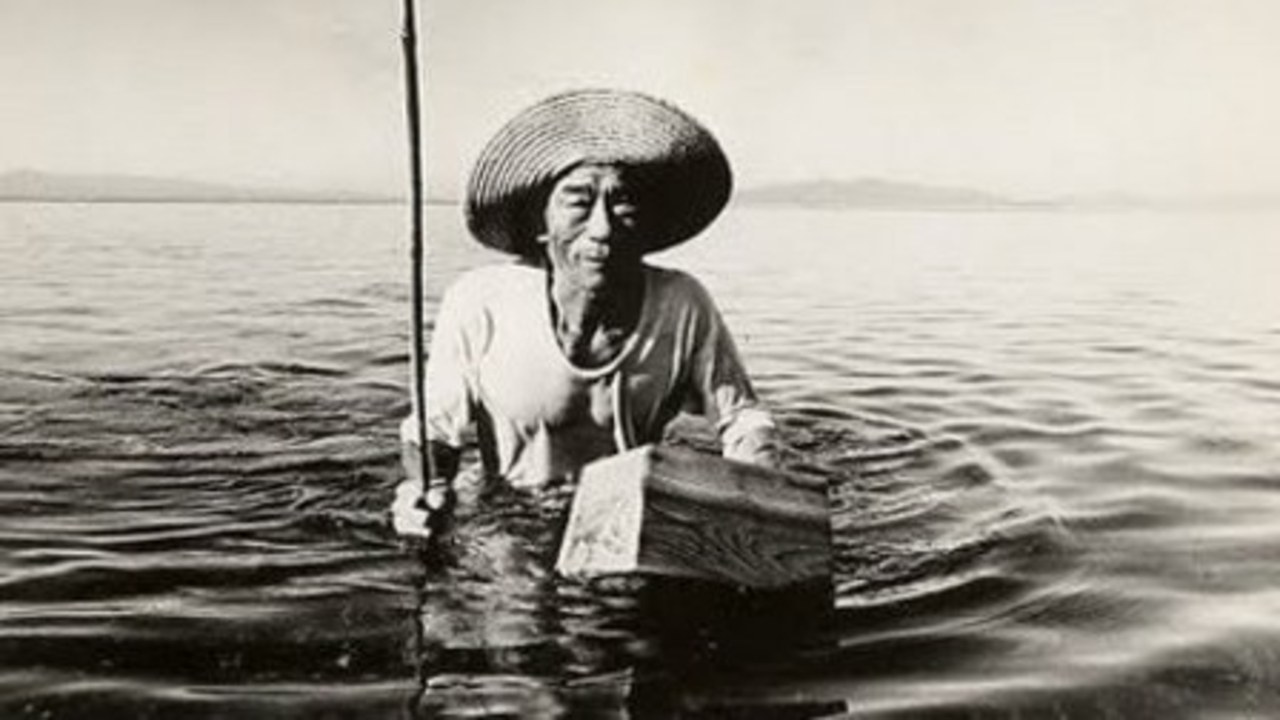

‘Minamata: The Victims and Their World’, 1972

Noriaki Tsuchimoto was a law-school graduate and student activist before discovering his passion for filmmaking, which he approached with a clear socio-political vision of the role that cinema and the media might have. Mr Tsuchimoto was one of the first who recognized the soft power that this medium held, if wielded properly. He’s best known for his work documenting the mercury poisoning effects on Minamata, a fishing community on Kyushu’s west coast, where he made over fifteen films across decades.

‘Minamata: The Victims and Their World’ is deeply troubling and extremely important to its genre, as the director is intent on documenting the daily lives of those devastated by exposure to such poisonous industrial waste. He refuses to gloss over the banality and tranquillity of their lives while also underlining their gradual radicalization. In one scene, the villagers confront the corporation responsible—a startling and painful event to watch. The victims desperately plead for any kind of reaction to their situation, while Chisso’s representatives carry through their shareholder meeting without responding, publicly and shamelessly choosing to ignore the death and disfiguration that their company directly caused. Sadness and indignation can’t not move us at this point.

‘MINAMATA: THE VICTIMS AND THEIR WORLD’ (1972), ©HIGASHI PRODUCTIONS

‘MINAMATA: THE VICTIMS AND THEIR WORLD’ (1972), ©HIGASHI PRODUCTIONS

‘In the Realm of the Senses’, 1975

One of the few truly hardcore art films came out of Japan, boldly signed by Nagisa Oshima. ‘My hatred for Japanese cinema includes absolutely all of it’, the director once said. In his mind, it was nothing more than a wasteland of samurai epics, bleak parlour dramas, and the occasional monster. His movies thus determined to be packed with all the vim, passion, and petty cruelties of a less mellow culture. They became cult icons of Asia and beyond. Oshima’s work gleefully coincided with the relaxation of censorship laws against pornography in the mid-Seventies, and he did not hesitate to take a chance and finally treat sex on screen with the unrestricted realism that it deserved.

Enter ‘In the Realm of the Senses’, an adaptation of the true story of a prostitute named Sada Abe, who was arrested in 1936 whilst wandering down the street with her lover’s severed genitals tucked in her kimono. Naturally, the end result was a hardcore allegory about obsession, sadomasochism, and the inherent splendour of death and bloodshed. But the film never aimed to just thrill its viewers. It was also one massive middle finger dedicated to the mainstream’s cultural taboos on certain aspects of eroticism.

‘IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES’ (1976), ©OSHIMA PRODUCTIONS

‘IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES’ (1976), ©OSHIMA PRODUCTIONS

‘The Man Who Stole the Sun’, 1979

Kazuhiko Hasegawa is famous for two thoroughly underrated gems of Japanese cinema in the Seventies. One of them is ‘The Man Who Stole the Sun’. Masquerading as a dazzling and provocative action epic, this particular work manages to impress through its handling of nuclear fear. The anti-hero learns to quit worrying and embrace the bomb. It utilizes its action thriller template in a way I’ve not seen before, delivering a troubling combination of comedy and suspense slightly akin to John Frankenheimer’s ‘The Manchurian Candidate’ (1962). However, that daring weirdness is precisely where the similarities end.

The story follows a high-school science teacher who manages to build an atomic bomb and demands… well, it turns out he’s not sure what he wants! A cat-and-mouse game with a police inspector ensues—played brilliantly by action icon Bunta Sugawara, quickly evolving into a counter-culture satire that whacks us with its merciless punchline. Our anti-hero is stumped and ends up asking for a cancelled Rolling Stones concert to take place. My favourite and, at the same time, deeply troubling part is watching the teacher as he knowingly cuddles up with his nuclear ball for a bit of shut-eye.

‘THE MAN WHO STOLE THE SUN’ (1979), ©TRISTONE ENTERTAINMENT INC.

‘THE MAN WHO STOLE THE SUN’ (1979), ©TRISTONE ENTERTAINMENT INC.

‘Director Yasujiro Ozu’ by Shigehiko Hasumi Is Published, 1983

This was easily the book that singlehandedly influenced modern Japanese cinema, yet it is exceptionally rare for a critical study of a film director to have such an impact on not only how movies are discussed, but also how they are made. Mr Hasumi, a scholar of French literature at the University of Tokyo, accomplished just that.

His most notable achievement is countering conceptions of the legendary Yasujiro Ozu as either a minimalist or the ‘most Japanese’ of directors. To do that, Mr Hasumi dug deep into the director’s basis in cinema and argued plainly that anything Japanese was less a reflection of Japan than a product of film and Ozu’s unique manipulation of visual and narrative motifs. Ultimately, the book forever altered future filmmakers’ impression of Yasujiro Ozu. The likes of Masayuki Suo and Naoto Takenaka chose to emulate Hasumi’s version of Ozu, as opposed to the real one. Many post-Eighties directors who studied under Hasumi followed a similar path, and his influence can be easily spotted in their films.

LEOS CARAX AND SHIGEHIKO HASUMI, ©MICHIKO YOSHITAKE

LEOS CARAX AND SHIGEHIKO HASUMI, ©MICHIKO YOSHITAKE

But what I perceived as simply the greatest shift of all was the emergence of ‘Akira’ (1988). From that moment on, it became clear that Japan’s most valuable export would soon become the animation—the beloved anime, specifically, that went on to birth entire cultures online and across the globe. It started with a bang, quite literally, in ‘Akira’, and it hasn’t stopped since.

In the end, Japan has had nothing but good and wonderful things to give us, in its own definitive and impossible-to-confuse style. From its black-and-white minimalism to its thespian explosions of colour and its often incredibly ambitious themes, it’s plain to see how Japan made its indelible mark on the silver screen. Film is but a medium, and the Japanese proved that it is how you use it that makes it a triumph.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.