The ‘60s brought changes in culture and style that affected even the world of film music. The sound of the symphonic score established in the ‘30s by the likes of Max Steiner was going out of fashion, being instead replaced by experimental music, jazz- and rock-oriented rhythms, and pop tunes. Composers like John Barry, Ennio Morricone and Jerry Goldsmith were strongly influencing the cinematic sound of the decade and what the studios would request from their directors.

The following selection includes some of the most famous rejected scores of the ‘60s, underlining the strong creative differences between directors, composers and studios, which ultimately influenced the outcome of each production.

‘EL CID’ MOVIE POSTER

‘EL CID’ MOVIE POSTER

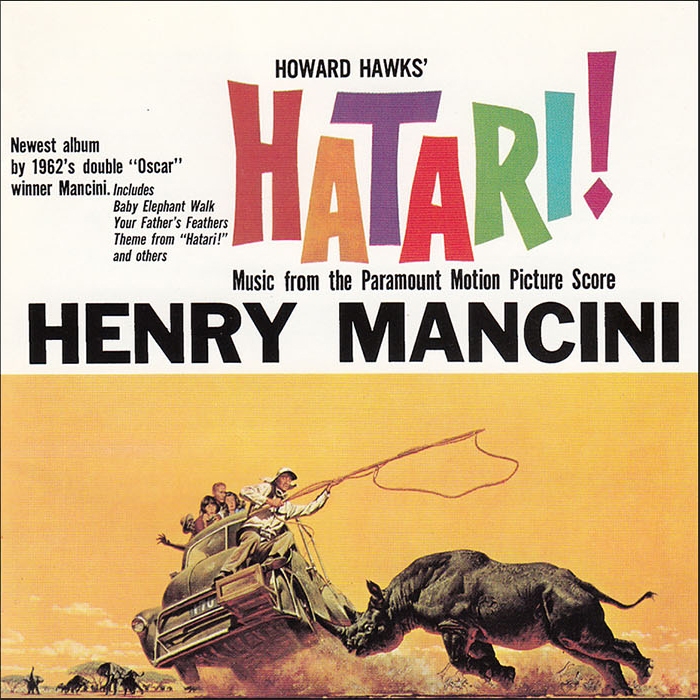

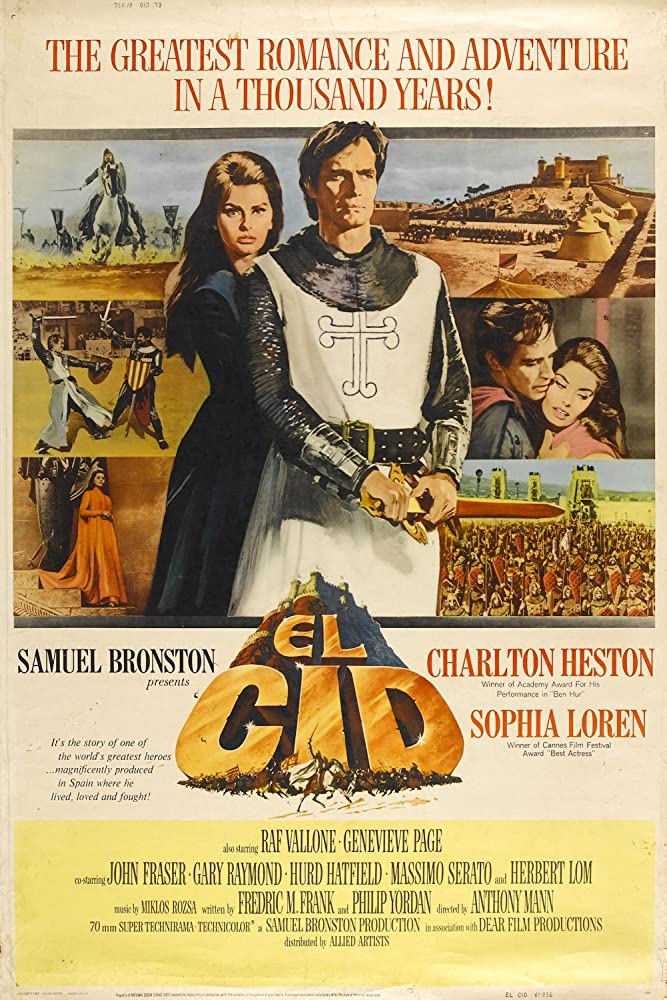

El Cid (1961)

Miklós Rózsa

Mario Nascimbene

Directed by Anthony Mann and produced by Samuel Bronston, El Cid is a 1961 epic historical drama film that is based on the life of the Castilian knight Don Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, called ‘El Cid’, who sets upon defending Christian Spain against the Moors.

Samuel Bronston had just finished his epic film King of Kings (1961), and decided to materialise his life-long dream of bringing the story of El Cid to the big screen. MGM had partially financed King of Kings, which meant they had a say in every major decision. Wanting more freedom and control over this new epic, Bronston produced El Cid with his own company, Samuel Bronston Productions, in association with the Italian company Dear Film Produzione. This meant that in order to receive financial assistance from the Italian government, certain compromises had to be made, such as Bronston having to employ a certain number of Italian artists and technicians to work on the project. As such, despite wanting to hire Miklós Rozsa, with whom he had worked on A King of Kings, Bronston went ahead and hired the Italian composer Mario Nascimbene. This collaboration, however, would be short-lived, as Bronston’s requirements would infuriate the composer. Nascimbene writes:

Bronston called me and asked me to score EL CID, which was being shot by Anthony Mann. I read the screenplay first, and they told me to write some dance themes only. The music had to accompany a kind of fighting dance for scenes taking place on the beach, so I wrote some cues for tympani, with a rather brutal, violent rhythm, without any real melody. Director Mann liked what I had written and shot his scenes, using the cues as background. Then, when shooting EL CID was about halfway, I was asked to come to Malaga to discuss the score itself. Samuel Bronston met me there when I arrived, showed me a pile of records of Massenet’s ‘El Cid’ and told me: “This is the music for the film”. Apparently I had to sort of “adapt” Massenet’s music for the film. Samuel Bronston behaved in an offensive way, and I told him that I am used to discussing the score with a director, and with him only. So I returned to Rome, where I tore up the contract already made.

This outcome worked wonderfully for Bronston, who managed to hire his first choice, Miklós Rózsa. It is speculated that the producer never intended for the score to be an adaptation of Jules Massenet’s opera to begin with, but it was merely a sure-fire plot to get Nascimbene to back out of the picture.

Be that as it may, Bronston did go to great lengths to get Rózsa to score his picture, even managing to get him out of a pre-existing contract with MGM to score Mutiny on the Bounty (1962). Mutiny would end up being scored by another MGM in-house composer, Bronislau Kaper. As a concession to their co-producers, another Italian composer’s name (Carlo Savina) appeared on the credits as co-composer on the picture, but only on the Italian prints.

Bronston flew Rózsa and his family to Madrid for the whole summer and offered him a lovely house for him to work from and the same weekly living expenses the producer himself was getting. Besides Spain itself being a huge inspiration for the score of El Cid, the composer set out to research the history of El Cid and the Spanish music in the Medieval Ages. He turned to ninety-two-year-old Dr Ramón Menéndez Pidal, a Spanish philologist, historian and expert in El Cid, who introduced him to the twelfth-century musical poems of ‘La Cantigas de Santa Maria’. Furthermore, Rózsa studied Felipe Pedrell’s collection of Spanish folksongs, which the musicologist had compiled throughout his life. The composer spent a month of intense study, analysing these two very different sources after which he began working on translating what he had learned into the new score.

Despite Rózsa’s seamless collaboration with Bronston, the composer was shocked to realize, during the premiere of El Cid, that the director and his sound editor had chopped and binned some of Rózsa’s cues in favour of the film’s sound design. As a result, Rózsa cancelled his publicity tour, stating that, ‘I could not talk about music which nobody was going to hear.’

The above issues notwithstanding, the film was a commercial success earning more than four times its production cost of $6.25 million and garnered three Academy Award nominations including Best Art Direction, Best Film Score and Best Song. El Cid would be Milós Rózsa’s last epic score.

‘HATARI!’ MOVIE POSTER

‘HATARI!’ MOVIE POSTER

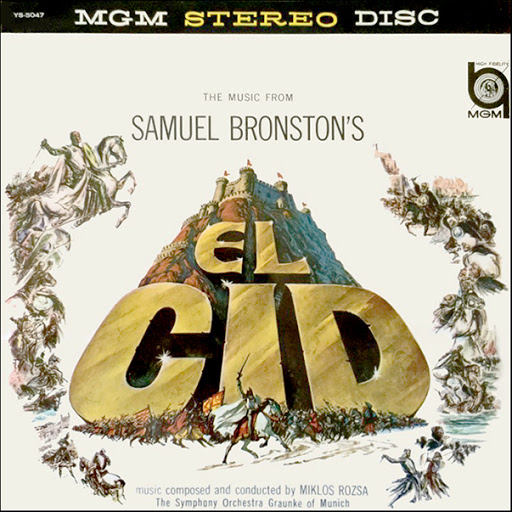

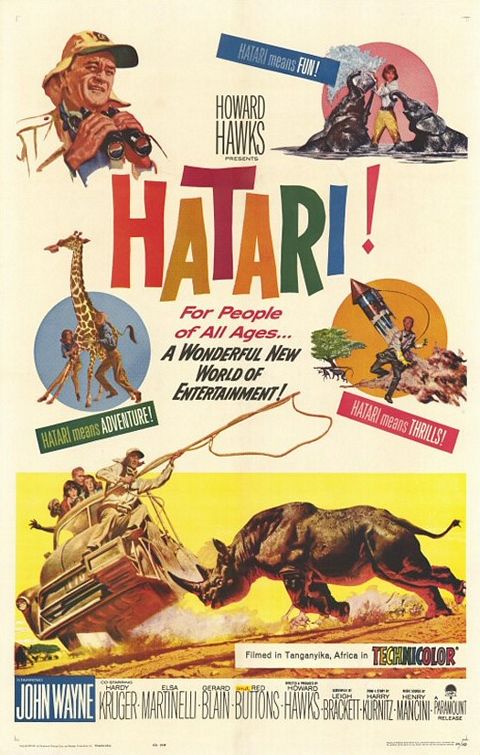

Hatari! (1962)

Henry Mancini

Hoagy Carmichael

Hatari! is a 1962 American adventure romantic comedy film directed by Howard Hawks. It portrays a group of professional game catchers in Africa who entrap wild animals and sell them to zoos before a female wildlife photographer disrupts their ways.

Hawks was planning on hiring his long-time collaborator, Dmitri Tiomkin, to write the score for the picture. The director’s only requirement was for Tiomkin to completely leave out the string and woodwind sections and instead use authentic African instruments. Thinking Hawks was joking, the conservative composer showed the director a score that included strings. This misunderstanding would lead to them parting ways and the pair would never work together again.

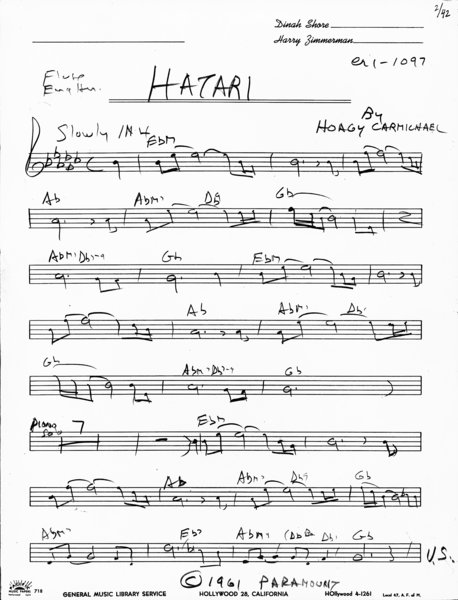

HOAGY CARMICHAEL’S SKECTH FOR ‘HATARI!’

HOAGY CARMICHAEL’S SKECTH FOR ‘HATARI!’

The director then turned to prolific singer-songwriter Hoagy Carmichael who played Cricket in the director’s 1944 picture, To Have and Have Not, after Hawks had discovered the musician at a party. Hawks wanted to work with someone who had never scored a picture before and had no preconceived notions of what a score is supposed to sound like. And although the director was happy at first with Carmichael’s material, they ended up disagreeing on the direction of the music and Hawks had to turn to another composer yet again.

As it turned out, the third time was the charm as the director’s next choice, Henry Mancini, would go on to score Hatari!. Mancini did end up using violins in his music, however, he masterfully entwined them with tribal rhythms and an array of native instruments that Hawks had brought back with him from Africa. Mancini would use instruments such as the thumb piano, shell gourds and giant pea pods to score the animal scenes. Among the shot material was a scene that Hawks was contemplating on cutting out, but asked Mancini to have a look at it regardless. The scene featured Anna Maria D’Alessandro (Elsa Martinelli) taking three small elephants to a watering hole to bathe them. The composer loved the scene and immediately knew what to do with it. He superimposed an E-flat clarinet over an electric calliope (the only one in the world at that time), and the result would give birth to one of cinema’s most memorable themes, ‘Baby Elephant Walk’. The composer recalled:

[…] As the little elephants went down to the water, there was a shot of them from behind. Their little backsides were definitely in rhythm with something. […] it reminded me of something. I though, Yeah, they’re walking eight to the bar, and that brought something to mind, an old Will Bradley boogie-woogie number called “Down the Road a Piece”, a hit record in the old days, with Ray McKinley on drums and Freddie Slack on piano. Those little elephants were definitely walking boogie-woogie, eight to the bar. I wrote “Baby Elephant Walk” as a result.

Interestingly, the next track after ‘Baby Elephant Walk’ on the soundtrack recording is ‘Just for Tonight’, which was Hoagy Carmichael’s reworking of ‘A Perfect Paris Night’ and the only material retained from his work in the film. Luckily, all of Carmichael’s recorded music, as well as the written score were preserved and are archived at Indiana University.

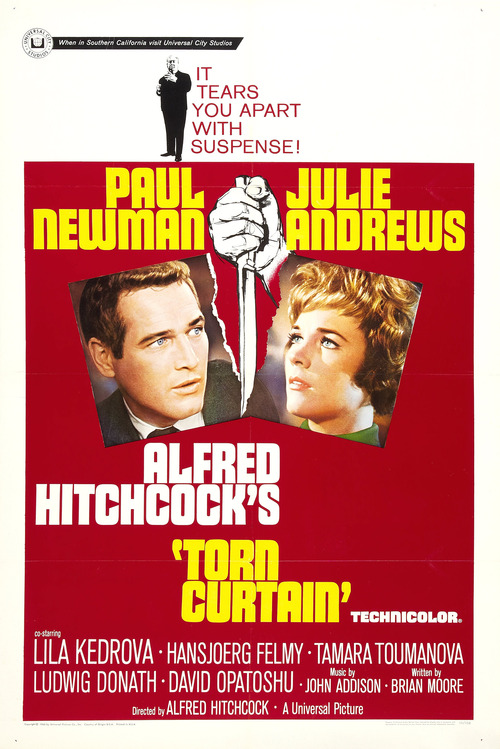

‘TORN CURTAIN’ MOVIE POSTER

‘TORN CURTAIN’ MOVIE POSTER

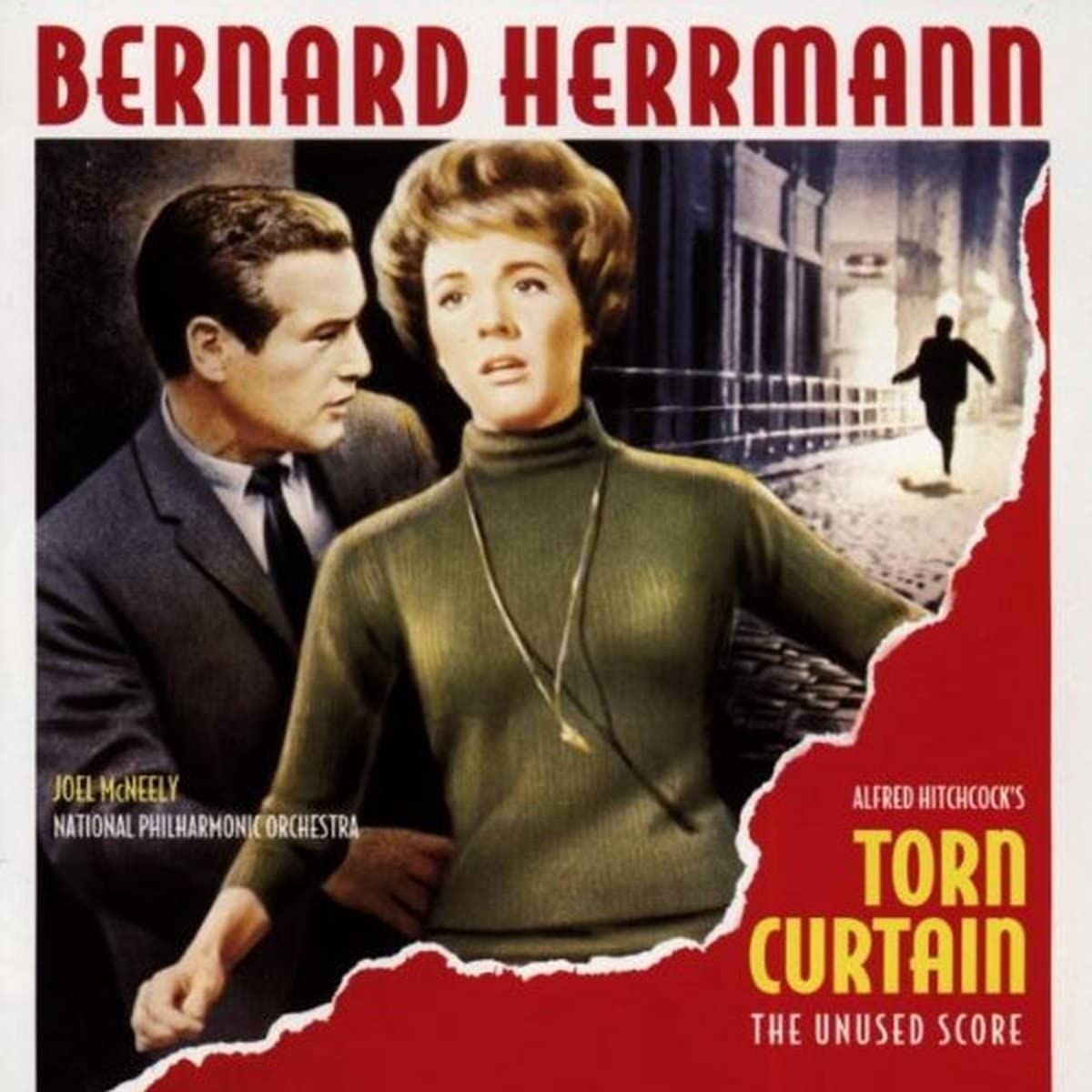

Torn Curtain (1966)

John Addison

Bernard Herrmann

Torn Curtain is a 1966 Cold War political thriller directed by Alfred Hitchcock. …of an American scientist (Paul Newman) who is secretly a double agent who publicly defects to East Germany to discover Soviet nuclear secrets.

By that time, the celebrated director had enthralled audiences worldwide with masterpieces such as Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959) and Psycho (1960). However, following the box office failure of Marnie (1964), Hitchcock started to doubt himself as his cinema was beginning to show its age. Universal Studios saw Hitch’s hesitation as an opportunity to get their claws into the film’s post-production. Lew Wasserman, the head of Universal, instructed Hitchcock to bring in a new sound to the picture and go for a pop-oriented score more in tune with the times.

Having previously successfully collaborated with Bernard Herrmann on eight of his pictures which constituted one of the greatest director-composer partnerships in the history of cinema, Hitchcock turned to the composer once again, this time with precise instructions in tune with the studio’s demands:

I am particularly concerned with the need to break away from the old-fashioned cued-in type music that we have been using for so long. […] The audience is very different from the one to which we used to cater; it is young, vigorous and demanding. It is this fact that has been recognized by almost all of the European filmmakers where they have sought to introduce a beat and a rhythm that is more in tune with the requirements of the aforesaid audience.

Herrmann was not crazy about the film but agreed to score it as by that time Hitchcock was his only regular source of feature film work. The independent-minded composer went ahead with music he thought was appropriate for the film. Granted, Hitchcock had asked Herrmann to sketch the music ‘in advance because we have an urgent problem of meeting a tax date’, so the composer had to come up with the cues blindly. When Hitchcock arrived at the Goldwyn Studios on 24 March 1966 for the first recording session, he was shocked to realize that Herrmann had gone against his wishes and wrote bold, unusual symphonic music using atypical orchestrations and an unorthodox line-up of instruments consisting of twelve flutes – doubling on piccolos, alto flutes and bass flutes – sixteen French horns, nine trombones, two tubas, double timpani, eight cellos and eight basses. He also composed music for the murder scene, even though Hitchcock had expressly requested be left without music.

The orchestra musicians were ecstatic about Herrmann’s score and gave him a standing ovation right after the recording. Hitchcock, however, was furious and dismissed the composer in front of everyone. The two never spoke again, ending a twelve-year-old collaboration.

A few days later, British composer John Addison was hired and flown to Los Angeles. Ironically, Addison’s replacement music wasn’t pop-oriented either and neither did it manage to salvage the picture which flopped.

Bernard Herrman’s score for Torn Curtain remains one of the best known ‘might have beens’ in the history of film music. And although it never ended up in the film, his music was released on CD no less than three times over the years.

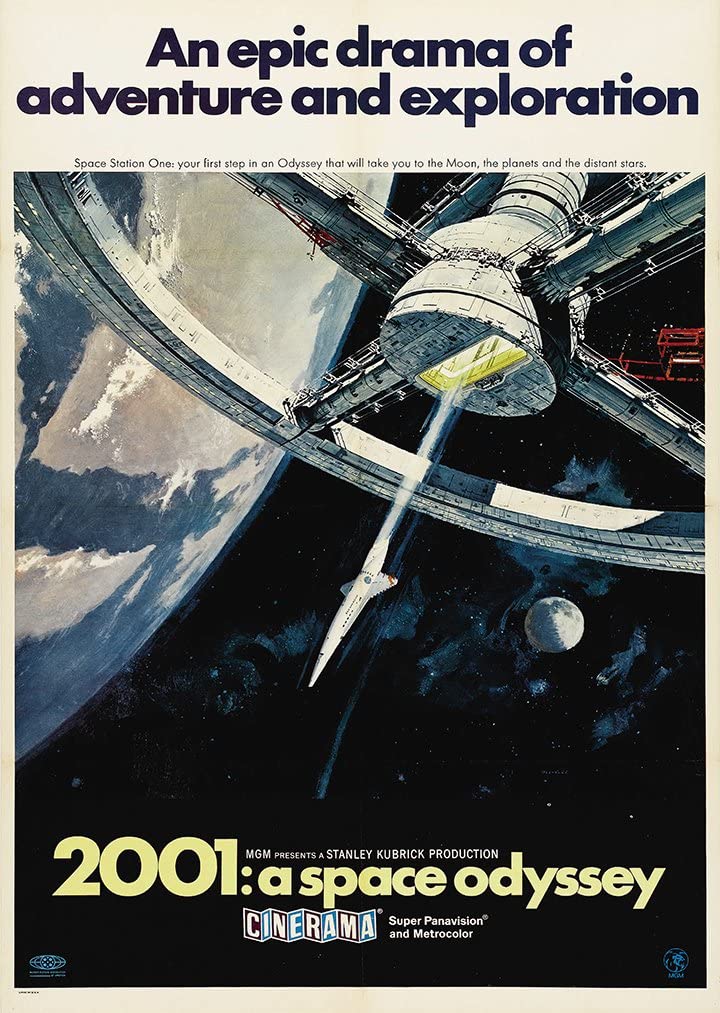

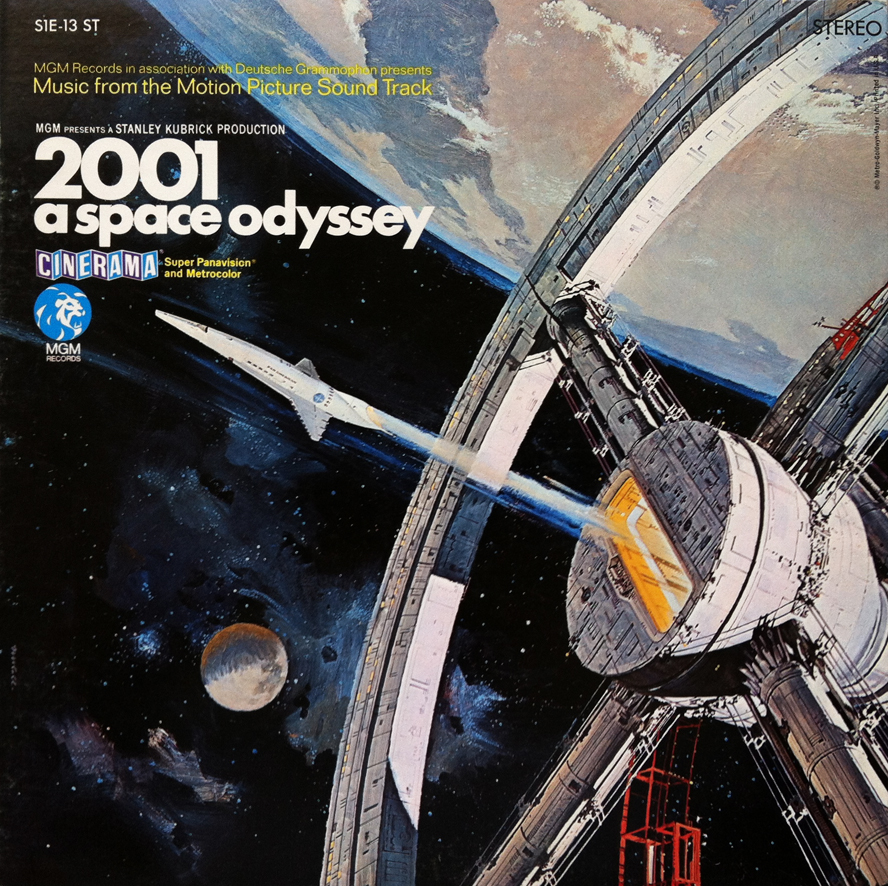

‘2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY’ MOVIE POSTER

‘2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY’ MOVIE POSTER

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Classical compositions by various composers

Frank Cordell, Alex North

2001: A Space Odyssey is Stanley Kubrick’s magnum opus and is based on Arthur C. Clarke’s short story The Sentinel. Kubrick worked together with Clarke on writing the script, which they completed in January 1966, which would eventually prompt Clarke to publish his science fiction novel 2001: A Space Odyssey.

As was his custom, Kubrick used temporary music throughout his film in order to find the film’s pulse and to help carry the narrative. And thus, over the next two years, as the project was taking shape, he acquired multiple records of classical music, listened to countless hours of orchestral pieces and put together a temp track (temporary music used in a picture during production). Among his favourites were Felix Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Richard Strauss’ tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra (which became the movie’s signature track), a waltz by Frédéric Chopin, Johann Strauss’ The Blue Danube, Aram Khachaturian’s Gayene, and Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana. Kubrick actually approached Orff and tried to persuade him to compose the score, however, Orff politely declined saying that this task was too large for his advanced age (the composer was seventy-one at the time).

Kubrick became convinced that his film didn’t need an original score as his carefully-curated selection of classical oeuvres would do the film justice. The MGM bosses, however, disagreed. They were adamant that a movie of such magnitude required an equally-great composer. And so, at the end of 1967, the director approached two composers – English composer Frank Cordell and well-established Hollywood composer Alex North (with whom Kubrick had worked on Spartacus (1960).

The collaboration with Cordell was stillborn, as at that time, Kubrick wasn’t very clear about what he wanted and instructed the composer to adapt Mahler’s Third Symphony. Cordell’s score got rejected and Kubrick then turned to Alex North.

Alex North recalls:

I was living in the Chelsea Hotel in New York (where Arthur Clarke was living) and got a phone call from Kubrick from London asking me of my availability to come over and do a score for 2001. He told me that I was the film composer he most respected, and he looked forward to working together. I was ecstatic at the idea of working with Kubrick again (Spartacus was an extremely exciting experience for me), as I regard Kubrick as the most gifted of the younger-generation directors, and that goes for the older as well. And to do a film score where there were about twenty-five minutes of dialogue and no sound effects! What a dreamy assignment, after Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, loaded with dialogue.

I flew over to London for two days in early December to discuss music with Kubrick. He was direct and honest with me concerning his desire to retain some of the “temporary” music tracks which he had been using for the past years. I realized that he liked these tracks, but I couldn’t accept the idea of composing part of the score interpolated with other composers. I felt I could compose music that had the ingredients and essence of what Kubrick wanted and give it a consistency and homogeneity and contemporary feel. In any case, I returned to London December 24th [1967] to start work for recording on January 1, after having seen and discussed the first hour of film for scoring. Kubrick arranged a magnificent apartment for me on the Chelsea Embankment, and furnished me with all the things to make me happy: record player, tape machine, good records, etc. I worked day and night to meet the first recording date, but with the stress and strain, I came down with muscle spasms and back trouble. I had to go to the recording in an ambulance, and the man who helped me with the orchestration, Henry Brant, conducted while I was in the control room. Kubrick was present, in and out; he was pressured for time as well. He made very good suggestions, musically. I had written two sequences for the opening, and he was definitely favorable to one, which was my favorite as well. So I assumed all was going well, what with his participation and interest in the recording. But somehow I had the hunch that whatever I wrote to supplant Strauss’ Zarathustra would not satisfy Kubrick, even though I used the same structure but brought it up to date in idiom and dramatic punch. Also, how could I compete with Mendelssohn’s Scherzo from Midsummer Night’s Dream? Well, I thought I did pretty damned well in that respect.

In any case, after having composed and recorded over forty minutes of music in those two weeks, I waited around for the opportunity to look at the balance of the film, spot the music, etc. During that period I was rewriting some of the stuff that I was not completely satisfied with, and Kubrick even suggested over the phone certain changes that I could make in the subsequent recording. After eleven tense days of waiting to see more film in order to record in early February, I received word from Kubrick that no more score was necessary, that he was going to use breathing effects for the remainder of the film. It was all very strange, and I thought perhaps I would still be called upon to compose more music; I even suggested to Kubrick that I could do whatever necessary back in L.A. at the M-G-M studios. Nothing happened. I went to a screening in New York, and there were most of the “temporary” tracks.

In an interesting twist, North found out that his score had been rejected only during the film’s premiere in New York, an experience that, according to author Michael Benson, left him ‘shocked and humiliated’.

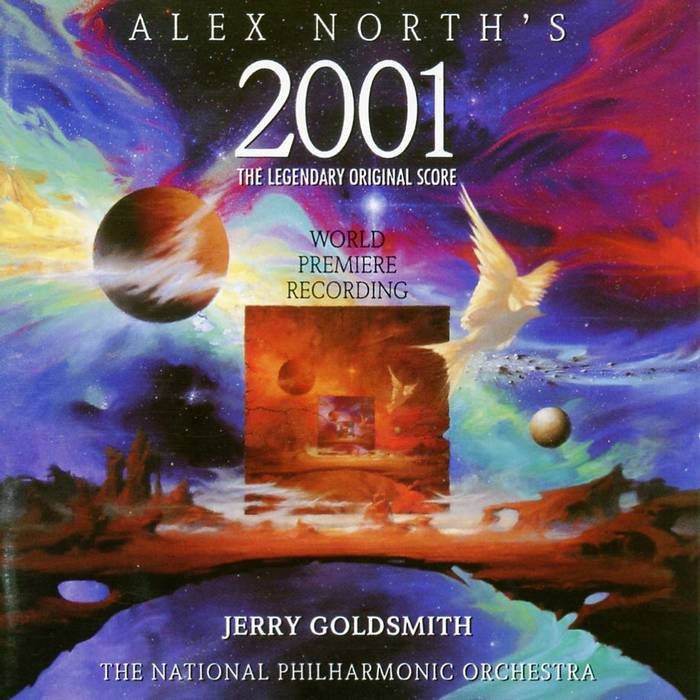

Thankfully, Alex North’s original score was brought to life in 1993 via a full recording conducted by Jerry Goldsmith.

Stella Lungu

Stella is the Editor-in-Chief of The Cinematic Journal. She is also the Managing Director of Wolkh, a PR, Marketing and Branding agency specializing in Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.