The western genre is not back, since it was never really dead, to begin with. Recently, several brilliant minds of contemporary cinema have tried their hand at bringing us tales from the scraggy and ever-dangerous Wild West, including Joel and Ethan Coen‘s ‘The Ballad of Buster Scruggs’ (2018). But it was ‘The Sisters Brothers’, by Jacques Audiard, that showed us how a whole new level of the genre can be reached–a level we didn’t even know existed.

In short, a Frenchman took a Canadian novel, filmed it in Spain, Romania, and France, then came out as one of the big winners of last year’s Venice Film Festival, depicting a most realistic, equal parts gritty and charming dark comedy set in America, during the Gold Rush.

But the film is much more than a mish-mash of multicultural efforts that successfully translated into a heartfelt ode to the classic western. ‘The Sisters Brothers’ is, quite frankly, a dollop of surrealism displayed through Jacques Audiard‘s outsider lens of amusement, as he pokes fun at his supposedly dangerous and highly skilled assassins, Charles and Eli Sisters.

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

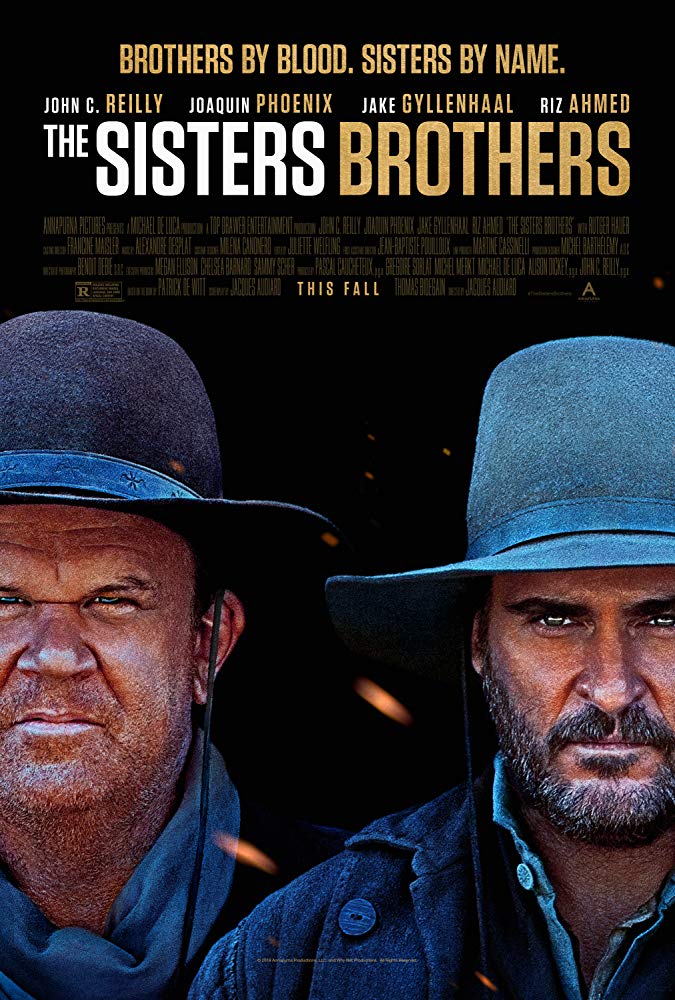

Based on the eponymous book by Patrick deWitt, ‘The Sisters Brothers’ follows two brothers and hired guns, played by Joaquin Phoenix and John C. Reilly, on their long and complicated journey as they track down a certain Hermann Kermit Warm, exquisitely portrayed by Riz Ahmed, with the help of Jake Gyllenhaal as the pretentious private detective named John Morris.

The screenplay, crafted by Jacques Audiard and Thomas Bidegain, gives us a glimpse into the lives and relationships of Phoenix’s Charlie Sisters and Reilly’s Eli Sisters, whom we follow from the mountain ranges of Oregon all the way down the California coastline and into the heart of San Francisco.

We’re taken along for the ride through the dark and scruffy Wild West, and we’re surprised when we realise that the two gunmen, despite their apparent proficiency in their field, usually have no clear idea about what it is they’re doing. It is sheer dumb luck and a hiccup of fortune that they manage to survive their circumstances, as they spend most of their time bickering over topics that range from trivial to ridiculous. In one instance, Eli is quite miffed that his brother gets more money for the same job, thus making him the ‘lead killer’.

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

The Commodore, a mysterious figure with no lines in the movie, is played by Rutger Hauer. While we never hear him speak, we can tell that he’s someone to be feared and with remarkably deep pockets, which is probably why Eli and Charlie Sisters do his bidding. Joaquin Phoenix and John C. Reilly are masters of their craft, giving us two fascinatingly different people, bound by blood and the years they’ve spent together, killing the Commodore’s targets for money.

Reilly is the melancholic and downright tired Eli, who longs to settle down and try something that does not require all this unpleasant murdering. His heart aches for a certain lady teacher, from whom he’s kept a memento–which he’s adamant that it be referred to by its proper term, a ‘shawl’. He carries it with him, carefully folding it every evening and sniffing her perfume, still lingering in the fabric. Eli is fascinated by the progress of technology and civilisation. He’s the first of the Sisters lineage to use a toothbrush, and we’re almost as giddy and he is when he discovers the flushing toilet in their San Francisco hotel room.

CREDIT: MAGALI BRAGARD

CREDIT: MAGALI BRAGARD

Charlie, on the other hand, is the simpler fellow. Phoenix is a tour de force, giving us a heavy drinker who doesn’t see the point in or the appeal of doing anything other than killing people for money. He bears the emotional weight of his father’s death, drowning his demons and utter loneliness in alcohol. John Morris’s pompous letters irk him, and he’d love nothing more than to put a bullet through his head, simply for using those fancy words to talk down on him and his brother. However, when faced with a better financial opportunity, presented by none other than Hermann Kermit Warm and the aforementioned John Morris, we witness a radical change in Charlie.

The Gold Rush is realistically depicted in this story, and Charlie is an accurate embodiment of greed turning a man foolish enough to make horrible decisions that impact not only his well being but also the lives of those around him. In the end, ‘The Sisters Brothers’ leaves us with a bittersweet taste, like any good tale about redemption and the diverse pits of the human soul.

CREDIT: MAGALI BRAGARD

CREDIT: MAGALI BRAGARD

Needless to say, the performances were stellar from all points of view. Joaquin Phoenix and John C. Reilly gave us the Sisters Brothers in all their unwashed, flea-ridden glory, while Riz Ahmed and Jake Gyllenhaal’s dynamic made for a fascinating contrast. Not even their first time on the set together (they’d previously worked together on ‘Nightcrawler’ back in 2014), Ahmed and Gyllenhaal are mesmerising as the foresighted chemist and the overly educated lawman.

Aside from portraying Eli Sisters with such gruff ingenuity, John C. Reilly was the one who optioned the film rights to Patrick deWitt’s novel back in 2011, thus establishing himself as the driving force behind the movie before he was even cast as Eli Sisters. From thereon, Mr Audiard and Mr Bidegain did their marvellous job of adapting a Booker-nominated book into what brought the audience to a standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival of 2018.

‘The Sisters Brothers’ was nominated for a Golden Lion in the Best Film category, but it was Jacques Audiard who walked away with a Silver Lion for Best Director. Before that, the film had also swept the César and Lumiere Awards in France, gathering trophies for cinematography, production design, directing, and sound.

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

It goes without saying that each of these awards was more than well deserved. The cinematography, for example, stunningly executed by Benoît Debie, follows its own path away from the footsteps of John Ford, deep into the Wild West’s darkest corners with close-up shots that force us to peer into the very souls of Mr Audiard’s characters. Mr Debie keeps us in the moment and binds us to Charlie and Eli Sisters, not to mention Hermann Kermit Warm and John Morris. John Wayne might’ve scoffed at ‘The Sisters Brothers’, but, for this day and age, the old western tropes may not have worked as well as they used to.

Perhaps one of the film’s highlights, at least in this writer’s opinion, is the very end sequence at the Sisters’ family home, which is a single, continuous take. The actors had to switch costumes off-camera to create the impression of time passing, which, in turn, was splendidly conveyed and fluid.

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

CREDIT: ANNAPURNA PICTURES

Another noteworthy aspect of ‘The Sisters Brothers’, besides its screenplay, performances, and cinematography, was the production design, helmed by Michel Barthélémy. While Jacques Audiard gave us dark humour and brutal visuals in its quest to display the realisms of living in that age–complete with the wonders of discovering civilization’s more modern perks of the flourishing Golden Rush era, Mr Barthélémy, along with his talented team of art directors and set designers made it all feel, not just look, real.

The immersion was achieved through faithful reproductions of Oregon’s saloons at the time, through careful designs of San Francisco’s streets and hotels–making it seem like a wonder of the mid 19th century, much like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon or the Library of Alexandria in their time. To further complete the accuracy of the Gold Rush period, dozens of make-up artists and hairstylists were brought in, breathing literal life into Milena Canonero’s costumes.

With a playful, moody, and oftentimes deeply emotional score composed by Alexandre Desplat, there were plenty of reasons for ‘The Sisters Brothers’ to become an independent-film-turned-box-office-darling. Alas, despite its glowing reviews and impressive festival victory laps, it only grossed $7 million against its $38 million budget.

Even so, Jacques Audiard, better known for ‘A Prophet’ (2009), ‘Rust and Bone’ (2012), and ‘Dheepan’ (2015), has managed to deliver a cinematic story filled with gorgeously peculiar and unexpected twists through ‘The Sisters Brothers’–incidentally his first English-language film.

While it could easily be considered a personalised homage to the western genre that gave us ‘Stagecoach’ and ‘The Magnificent Seven’, among many others, Mr Audiard’s creation stands well on its own, offering a brutal, sincere, and mesmerizing version of the ol’ West.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.